26 Jan 2026

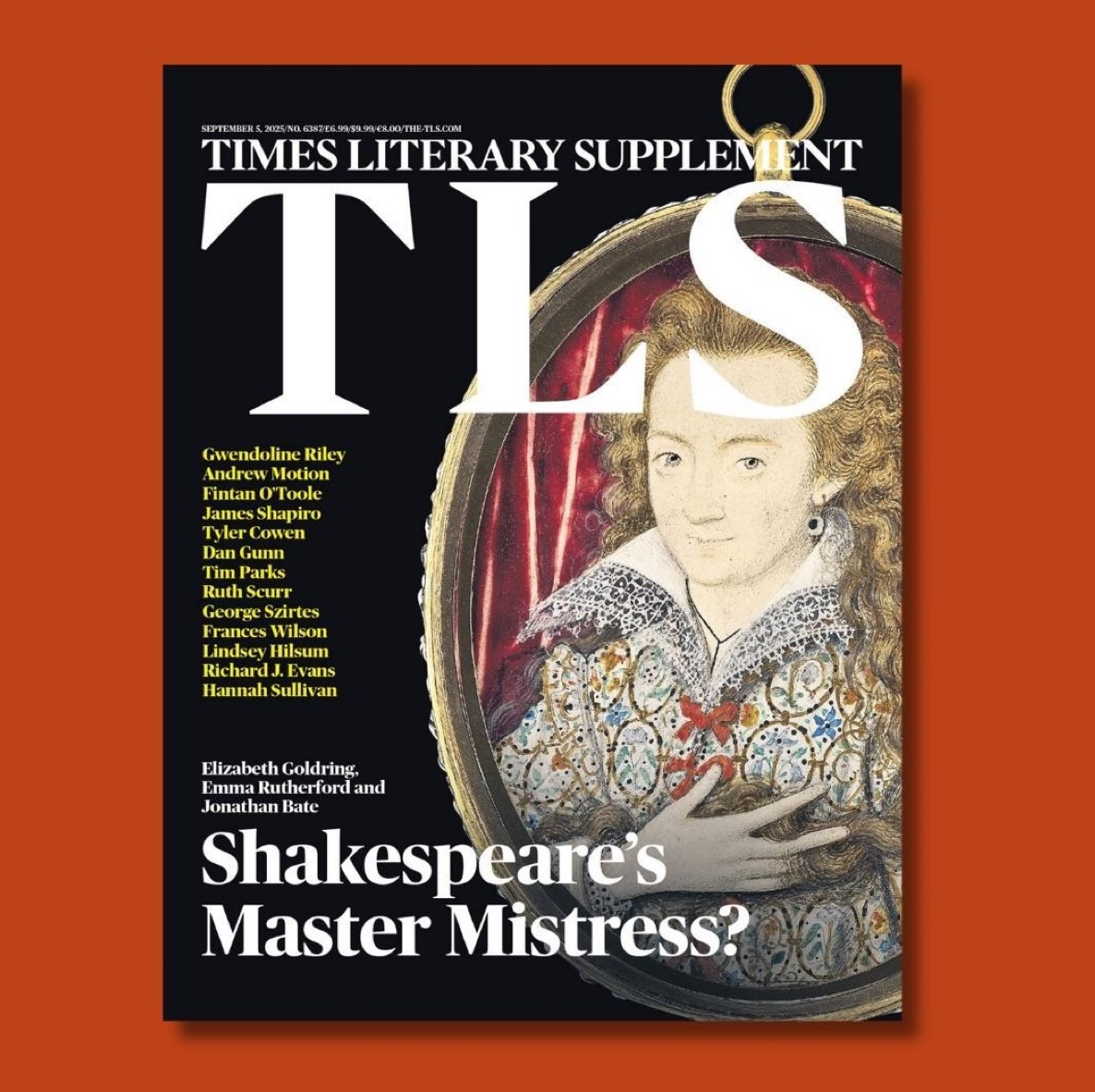

The Face of Fashion: Portrait Miniatures Centre Stage at Dior Haute Couture

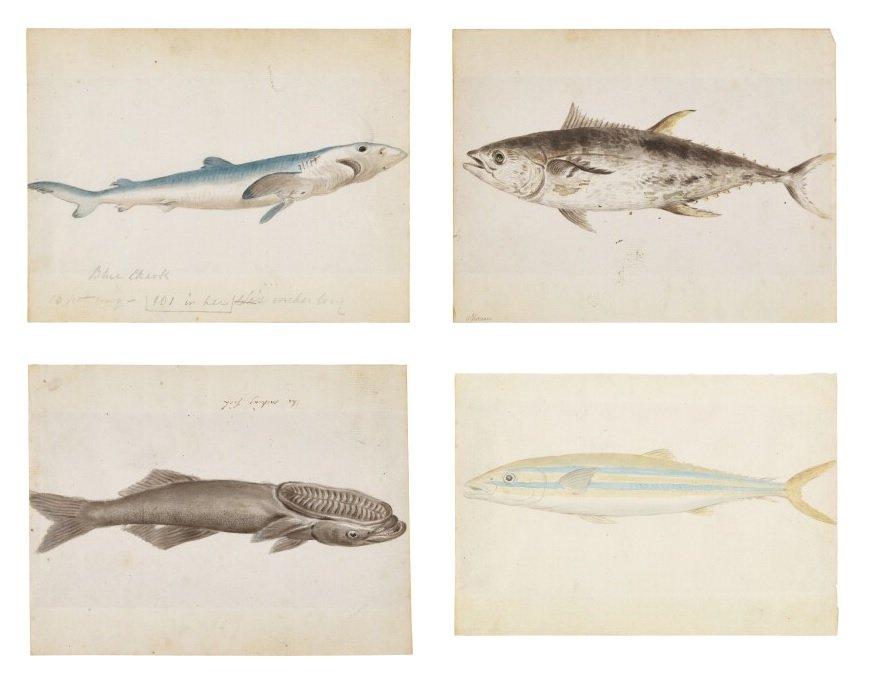

Today at the at the Musée Rodin in Paris, centuries-old art and contemporary fashion fused on the Dior runway which featured portrait miniatures recently sourced and sold by The Limner Company. Dior’s new Creative Director and leading light of British designers, Jonathan Anderson incorporated miniatures in his first women's haute couture show for the iconic fashion house, titled 'A Wunderkammer of Artefact and Nature'.

Instagram @vogueitalia

Instagram @vogueitalia

The Limner Company's director, Emma Rutherford, was a front-row guest at the show: "Today's Dior show has been a career highlight. To see portrait miniatures once again as wearable art, in this sophisticated, contemporary context reflects the visionary nature of Jonathan Anderson."

Get an exclusive look at the at the Dior miniatures below:

ROSALBA CARRIERA (1673-1757) Rinaldo and Armida; circa 1715 – recently sold by The Limner Company. More information in our new blog here.

ROSALBA CARRIERA (1673-1757) Rinaldo and Armida; circa 1715 – recently sold by The Limner Company. More information in our new blog here. ROSALBA CARRIERA (1673-1757) Portrait miniature of Joseph Smith and Catherine Tofts as Thalia – recently sold by The Limner Company. More information in our new blog here.

ROSALBA CARRIERA (1673-1757) Portrait miniature of Joseph Smith and Catherine Tofts as Thalia – recently sold by The Limner Company. More information in our new blog here.

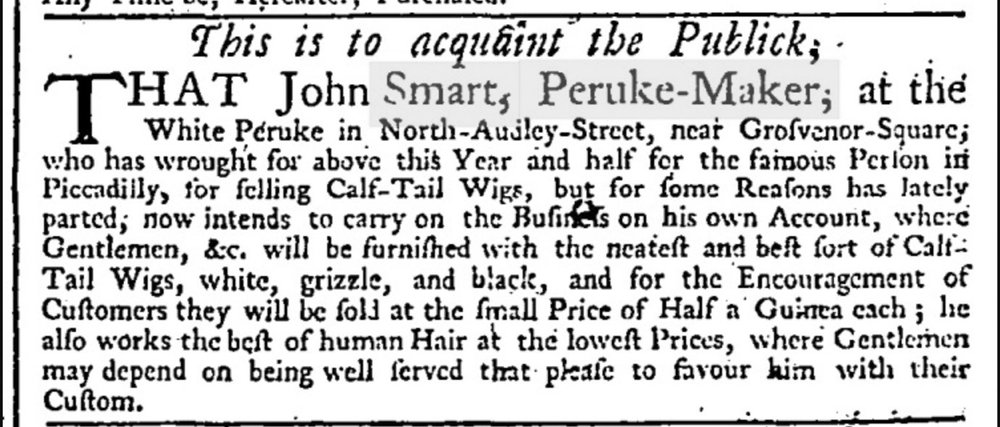

JOHN SMART (1741-1811) Portrait drawing of Mrs Elizabeth Shippey of Sloane Street, Knightsbridge, wearing a grey dress, black and white feathers in her powdered hair; 1784 - recently sold by The Limner Company, more information on our archive here.

JOHN SMART (1741-1811) Portrait drawing of Mrs Elizabeth Shippey of Sloane Street, Knightsbridge, wearing a grey dress, black and white feathers in her powdered hair; 1784 - recently sold by The Limner Company, more information on our archive here. Why Miniatures?

"Once again, I looked to the past to shape the future, this time with a greater sense of playfulness and the unexpected." - Jonathan Anderson [1]

Anderson frequently employs cultural touchstones in his work with a special interest in historical British art and craft. While Creative Director for Loewe, Anderson included several miniatures in his 2019 autumn/winter womenswear show titled, ‘The Best Self’ [pictured below]. Loewe had acquired a number of miniatures ahead of the runway show to which The Limner Company’s director, Emma Rutherford was invited.

In this context miniatures should not be mistaken for a gimmick, here they are prized in the multifaceted ways they were historically: personal expression and jewel-like beauty as well as artistry. As wearable art, they also align contemporary fashion design with one of the finest and oldest modes of self-presentation.

At once timeless artworks and intimate artefacts, portrait miniatures, eye miniatures, silhouettes and cameos have been increasingly catching the eye of the fashion world. Alessandro Michele, Italian fashion designer and Creative Director at Gucci (2015-2022), appears to be a collector of portrait minaitures which he wears frequently.

Instagram @alessandro_michele, 2022

Instagram @alessandro_michele, 2022 Instagram @alessandro_michele, 2017 & 2019

Instagram @alessandro_michele, 2017 & 2019Alexander McQueen often referenced memento mori in his work, including portrait miniatures and hair jewellery - see the Victoria & Albert Museum's online 'Museum of Savage Beauty' dedicated to the late deisgner.

Singer and beauty mogul, Rihanna has been influential in the 'cameo comeback'. Rihanna has long been wearing vintage jewellery but in 2019 she launched her own cameo collection with her brand, Fenty. The three pieces - a ring, a pair of earrings, and a pendant /brooch - were profile portraits of black women and described as 'miniature works of art that Rihanna hopes will be passed down through generations'.[1]

What is a Portrait Miniature?

Typically fitting into the palm of one’s hand, these small portraits have a long history dating back to the late 15th century (read more in our previous blog, 'Up Close and Personal: Portrait Miniatures in Context'). Most portrait miniatures were intended to be worn by both women and men, whether secretly or openly. Miniatures were usually commissioned by the sitter of the portrait with an intended recipient in mind.

Worn outwardly they displayed connections to loved ones, possibly a family member, spouse / betrothed, or a friend.Mothers and children...

Spouses...

Studio of SIR ALLAN RAMSAY 91713-1784) Portrait of a Lady, wearing a portrait miniature bracelet, and her Child; c.1760 - For sale with Period Portraits

Studio of SIR ALLAN RAMSAY 91713-1784) Portrait of a Lady, wearing a portrait miniature bracelet, and her Child; c.1760 - For sale with Period Portraits

JEAN-ETIENNE LIOTARD (1702-1789) Maria Theresa, Archduchess of Austria, Queen of Hungary and Bohemia, and Holy Roman Empress, wearing a portrait miniature of husband Francis Stephan; c.1745 - Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Germany.

JEAN-ETIENNE LIOTARD (1702-1789) Maria Theresa, Archduchess of Austria, Queen of Hungary and Bohemia, and Holy Roman Empress, wearing a portrait miniature of husband Francis Stephan; c.1745 - Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Germany.They were also often worn outwardly for diplomatic reasons, showing allegiance to a sovereign...

Attributed to DANIEL DUMONSTIER (1574-1646) Portrait of Baron Jean d'Harambure called the one-eyed (1553-1630), wearing a locket housing a portrait miniature depicting King Henry IV of France opposite his own portrait - Château de Versailles, France [1022152].

...a tradition which continues to this day...

In both these contexts, miniatures could also be concealed on the body, perhaps a talisman or token of loyalty to political cause - during the English Civil War for example or the Jacobite Rebellion.

They may also be exchanged and concealed as part of a clandestine love affair. In the case of the latter, they could be secreted in the bodice of a women’s dresses in the 16th and early 17th centuries - only a tantalising suggestion visible by the neck cord from which they hung disappearing into the wearer’s decolletage. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, lovers might wear a miniature depicting just the eye of their beloved. Often in highly bejewelled settings, a ‘lover’s eye’ as they became known, could be worn openly with the identity of the individual remaining anonymous.

The lover’s eye miniature must be a source of inspiration for Schiaparelli’s eye brooch ‘hero piece’[3]; a comparable 19th-century example can be found at the Victoria and Albert Museum [P.56-1977].

Highly-jewelled settings are often a giveaway for the intention of a miniature to be worn openly.

Model wears RICHARD COSWAY (1742-1821) Portrait miniature of a Gentleman, with the initials ‘CC’; circa 1790 - For sale The Limner Company, more information here.

Model wears RICHARD COSWAY (1742-1821) Portrait miniature of a Gentleman, with the initials ‘CC’; circa 1790 - For sale The Limner Company, more information here.

The concept of the portrait miniature remains prevalent in our day to day lives, perhaps without us realising. It’s genesis from manuscript illumination > portrait miniature > early portrait daguerreotype > photograph in your wallet > smartphone homescreen. Yet the ‘original’ portrait miniature remains a striking adornment today.

Browse wearable miniatures available now here.

Model wears THOMAS FLATMAN (1635-1688) Portrait miniature of a Young Gentleman, 1668 - For sale with The Limner Company, more information here.

[1] https://www.dior.com/en_gb/fashion/accessibility

[2] https://www.naturaldiamonds.com/culture-and-style/cameo-jewelry-history/

22 Jan 2026

Rosalba Carriera (12/01/1673-15/4/1757): Friend, Artist, Pioneer.

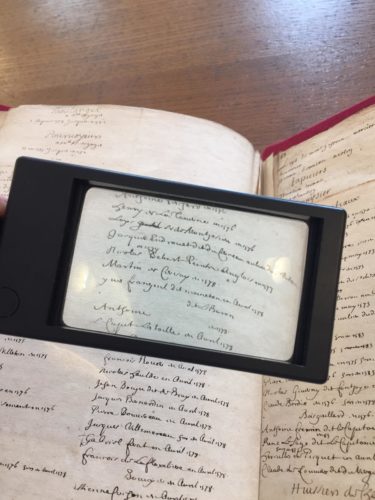

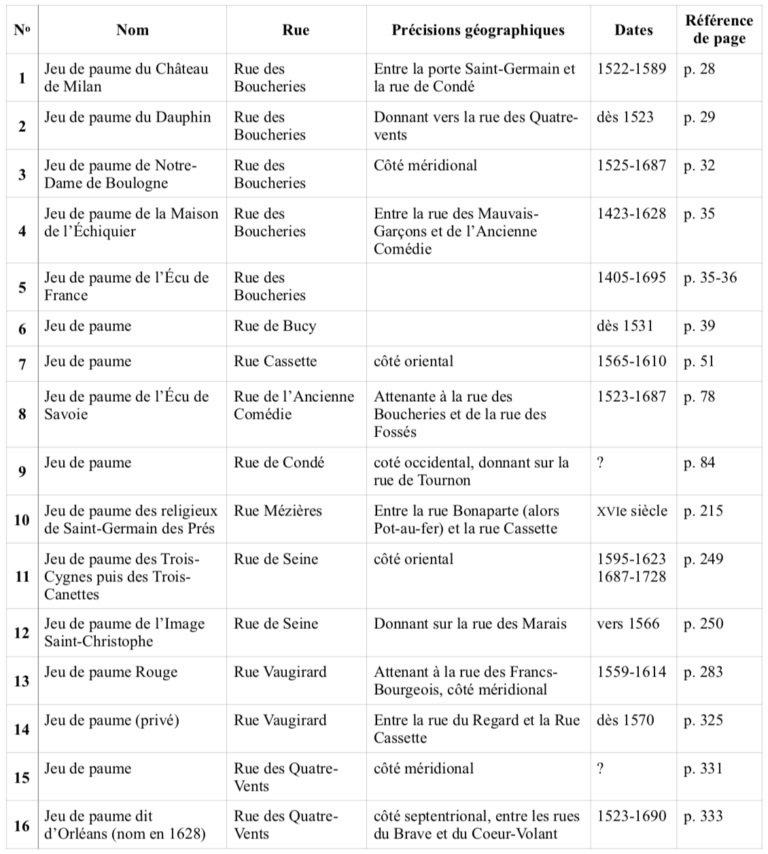

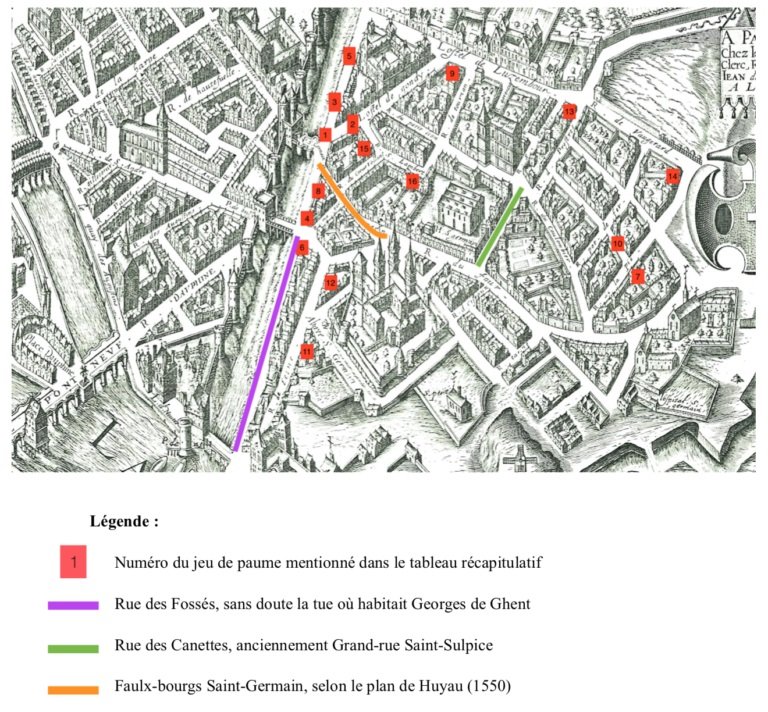

Rosalba Carriera’s lively, highly-coloured and distinctive portrait miniatures have been somewhat sidelined by her later biographers. She is best known to the art world now as a pastellist, and there are various volumes on her and her work in this form. In most of these, her work as a miniature painter is mentioned, though few studies have been dedicated entirely to her pioneering paintings on ivory[1]. The article below is inspired partially by four miniatures handled by The Limner Company over the past two years, and partially by the fact that few publications on the work of Carriera, especially that focus on her work in miniature, have been written in English[2].

The pastel portraits of Carriera are well-recognised for good reason, and they feature in important public and private collections across the world, including the Royal Collection, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden[3], and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Considering the fragility of the medium, it is impressive that so many of these portraits have lasted so long. This may have been helped by the fact that Rosalba presented these framed in order to protect them. Alongside her works in pastel, one can also find portrait miniatures in these collections, and the subjects of these range from myths to formal portraits. Looking through those illustrated in Bernardina Sani’s monographs, and recorded in the photographic files of the Witt Library, Heinz Archive and Library, and the Netherlands Institute for Art History, it became clear that the scope for creativity and playfulness within these miniatures was much greater for Carriera than it was in her work in pastel. Here, I will discuss this in relation to four examples, and suggest some possible reasons for this increased creativity, placing this within the context of Carriera’s success as an artist and strong network of colleagues, students, and patrons in the Venetian settecento.

Carriera’s early life

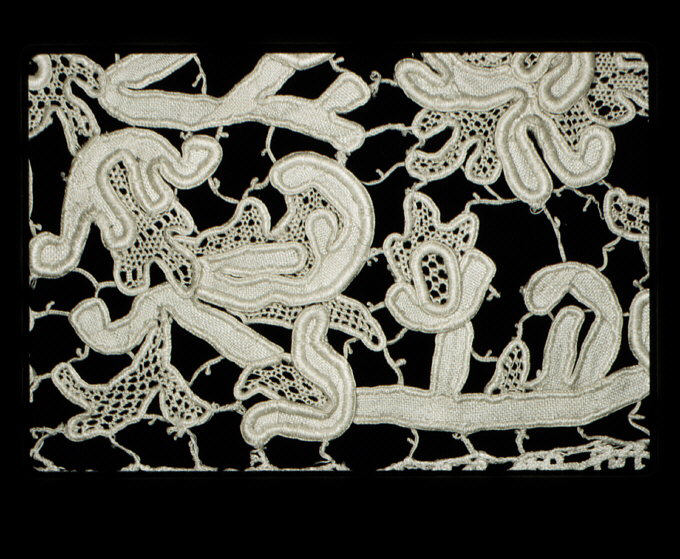

Carriera was born to a lawyer and a lace maker, and was the oldest of three sisters, Giovanna (1675-1737) and Angela. They grew up on the Grand Canal, and Carriera’s first employment in any form of art or craft came through her mother. She was a maker of Venetian lace, and it is said that Rosalba was particularly talented at making this. It is not surprising that she was able to adapt her skills to the delicate mediums of pastel and miniature painting if she was so adept in creating this fine material. Furthermore, and as will be seen below, Rosalba used her knowledge of lace within her portraiture, and this allowed her to add an extreme level of informed detail to the lace depicted in the costumes of her sitters.

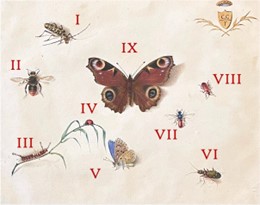

Fig. 1: A Fragment of Venetian Lace, first quarter 18th century, Metropolitan Museum, New York, number 88.1.6.

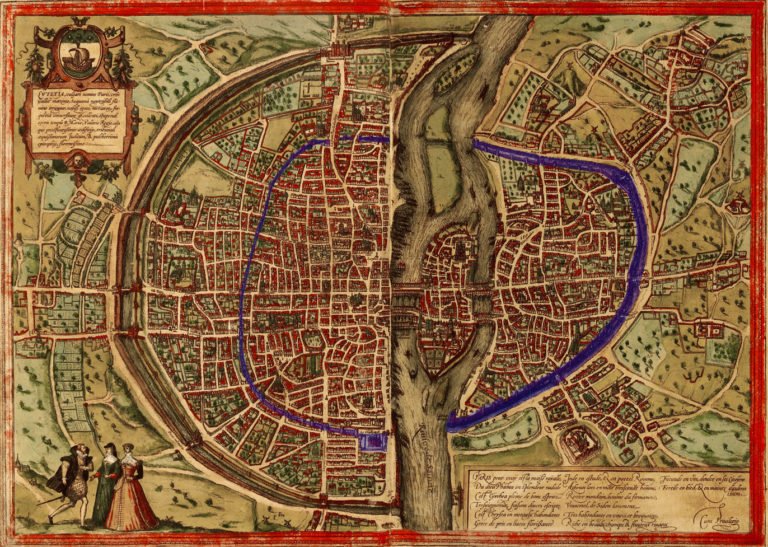

Angela Carriera married Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1685-1741), another famed Venetian artist, in 1704. This marks one of the first ties between her and the wider network of art and artists in the Venetian settecento. Alongside Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734), Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto (1697-1768), Jacopo Amigoni (1682-1752), Pietro Longhi (1781-1785), and Luca Carlevarijs (1663-1730), Pellegrini was one of the great (male) artists of his generation working in the city. As a hub for tourism, they all had access to the patronage of not only Italians but also global clients.

For Pellegrini, it was the English Charles Montagu (1656-1722), 1st Duke of Manchester, who eventually moved him to England to work on the walls and ceilings of his home, Kimbolton Castle. When Manchester arrived in Venice in 1697 as Ambassador, his secretary was Christian Cole (1673-1734), who had an interest in art and is reported to have been a pastellist himself[4]. He is a relevant character as he became a friend to Rosalba, possibly through Pellegrini, and eventually supported her in applying to the Accademia di San Luca in Rome in 1705.

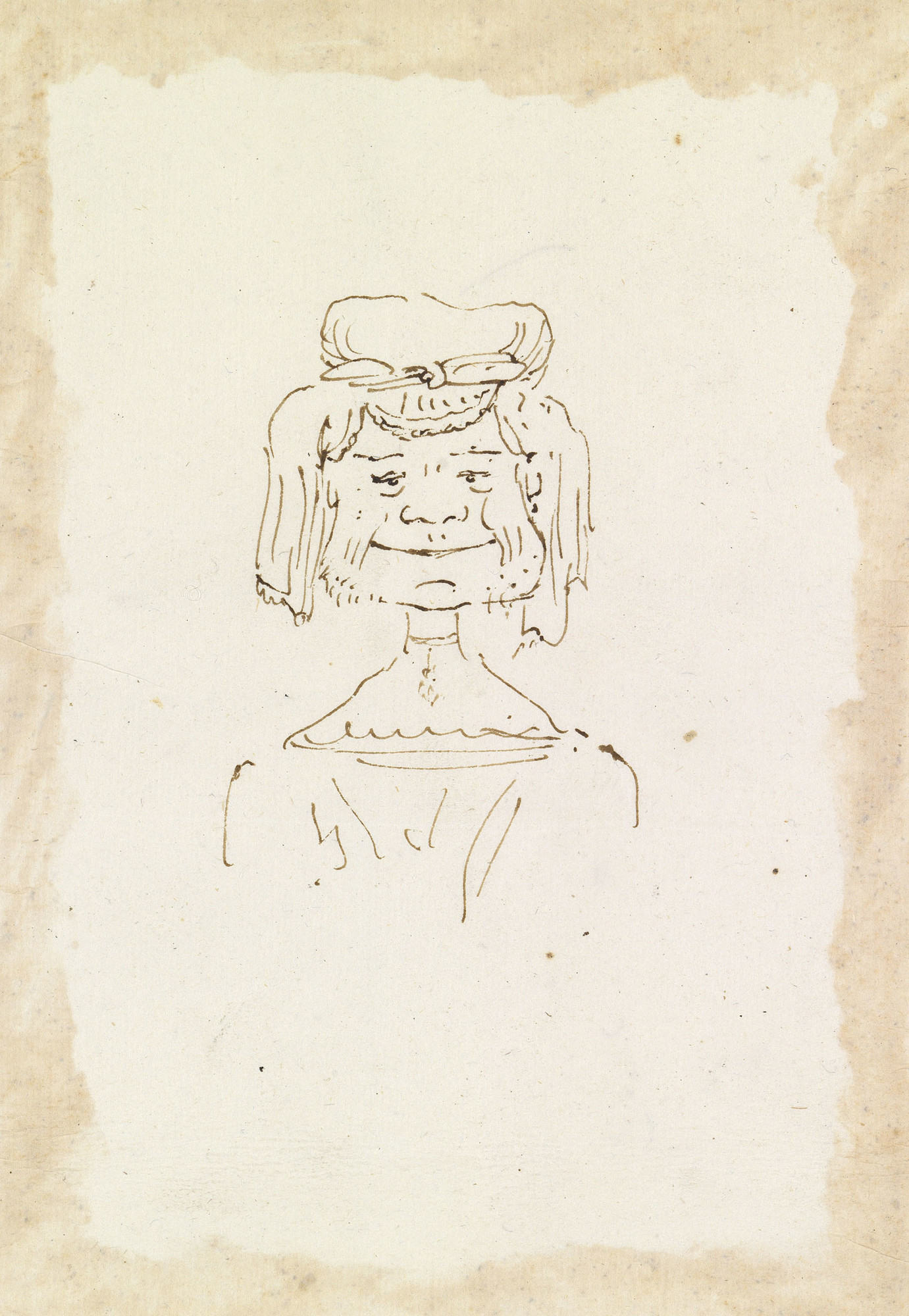

Fig. 2: ANTON MARIA ZANETTI THE ELDER (1680-1767), Rosalba Carriera c. 1730-40, pen and brown ink, 20.2 x 14.0 cm (sheet of paper), Royal Collection, RCIN 907390.

As Rosalba’s career developed, she fostered more friendships and relationships with other artists and influential figures across Europe. In Venice, one of these was Anton Maria Zannetti the Elder (1680-1767), who was clearly close to Carriera, given the existence of an amusing but brutal caricature of her now in the Royal Collection (fig. 2). Elsewhere, she maintained a friendship with Antonie Watteau, whom she had met in France in 1720, where she had been invited by Pierre Crozat (1661-1740) and Felice Ramelli (1666-1741), who was a student as well as a friend. Despite her close male friendships,, Carriera never married. There have been numerous theories as to why this was the case, many explained by Oberer (2023), including a suggestion that she was a lesbian and theories about her beauty (or lack thereof[5]). Neither of these seem to provide a factual basis for Carriera’s marital status. Perhaps she just never wanted or had time to find a husband, just as Canaletto never found a wife.

The Emergence of Carriera’s Miniature Painting

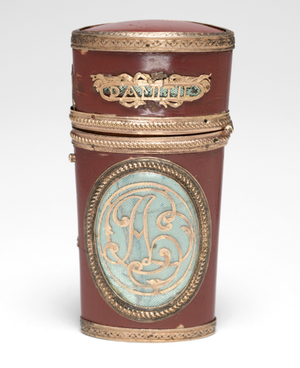

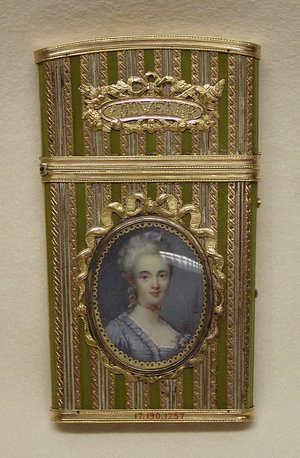

Carriera’s artistic career emerged in her late 20s; her first great professional ‘success’ in miniature painting was the Girl with a Dove[6] submitted to the Accademia di San Luca, Rome in 1705. Her work was well received, and she was admitted to the academy on merit, a first for a female artist. It has already been mentioned that Christian Cole was one of the people who pushed Carriera to go for this position and to move away from the purely commercial painting of miniatures for snuffboxes that she had focused on before this time.

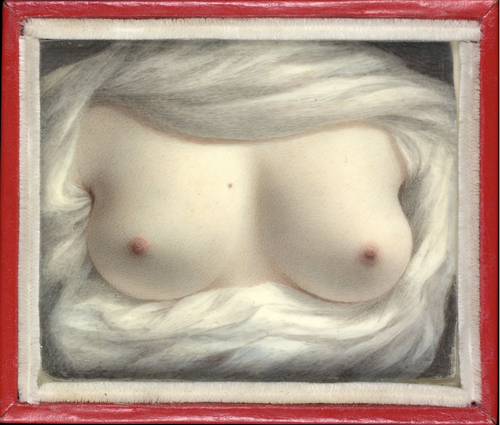

The Girl with a Dove is not completely separate from her early works, which were popular for their depictions of young peasant women. A leaf through any catalogue featuring Carriera’s works will reveal numerous miniatures of these types; other famous examples include The Peasant Girl in the Uffizi. Referred to by Rosalba and contemporaries as ‘Fondelli’, these portraits were painted on the inside of ivory snuffboxes, decorated with pique on the lids. Many of Carriera’s later works still featured this decoration on the reverse (see figs. 3 and 4), likely because she sourced her ivory for painting miniatures from the same workshops producing these snuffboxes.

Fig. 3: Reverse of ROSALBA CARRIERA, Portrait miniature of a lady in Venetian dress, c.1710-20, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, oval, 3 5/8 in. (94 mm) high, sold by The Limner Company.

Fig. 4: Reverse of ROSALBA CARRIERA (Venice 1673 - 1757), Portrait of Joseph Smith and Catherine Tofts as Thalia, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, oval, 3 3/8 x 4 1/2 in (8.5 x 11.5 cm), researched by Stephane Renard, Mrs. Bożena Anna Kowalczyk, attribution confirmed by Bernardina Sani.

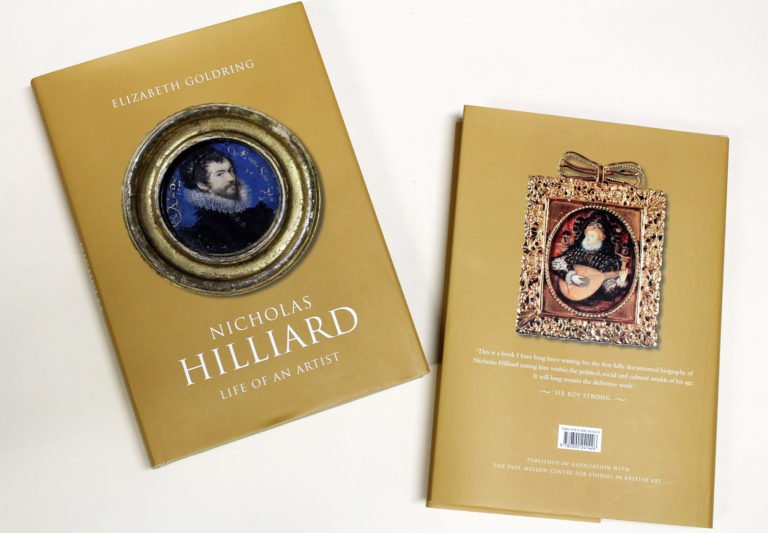

As hinted earlier, Carriera’s work on ivory is praised as the first of its kind. This is not to say that no one had painted in watercolour on ivory before; examples of other snuffboxes from the seventeenth century from the Ca ’Rezzonico’s 2023 exhibition show this was common form of painting, however these are very primitive in comparison to Carriera’s artworks. What was distinctive about Carriera’s approach was her removal of fondelli from their boxes, and development of portraits in their own right on this scale. In her diaries and letters, she referred to these portraits as miniatura; placing them into the same genre as the works of Nicholas Hilliard, Samuel Cooper, and other great artists who had come before her. Patrons soon began to request larger pieces of ivory that would ‘serve for a cabinet and not for a snuffbox[7]’, indicating that she was now producing pieces in their own right.

Some examples of miniatures by Carriera

Fig. 5: ROSALBA CARRIERA (1673-1757), Rinaldo and Armida, circa 1715, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, associated silver frame, oval, 3 1/8 x 2 3/8 in (8 x 6 cm).

Possibly one of the earliest of the miniatures by Carriera is this scene depicting Rinaldo and Armida (fig. 5). This is one of two miniatures painted by Rosalba of the same subject, the other being in the collection of the Dukes of Devonshire at Chatsworth. They vary slightly, in that the Chatsworth miniature displays Rinaldo looking at Armida, whereas this version sees him looking at himself in the mirror Armida holds.

The story of Rinaldo and Armida comes from Torquato Tasso’s (1544-1595) epic poem ‘Jerusalem Delivered’ (‘La Gerusalemme liberate’), published in 1581. In the poem, Armida, Muslim woman, enters a Christian camp and falls in love with Rinaldo, after distracting and transforming the knights into animals using magic. The sixteenth song of Tasso’s poem describes the pair meeting:

‘A crystal mirror, bright, pure, smooth, and neat, (Un cristallo pendea lucido et netto).

He rose, and to his mistress held the glass, (Sorse, e quel fra le mani a lui sospese)

A noble page, graced with that service great; (A i misteri d'Amor ministro eletto)

She, with glad looks, he with inflamed, alas, (Con luci ella ridendi, ei con accese) Beauty and love beheld, both in one seat; (Mirano in vari ogetti un solo oggetto) : Yet them in sundry objects each espies, (Ella del vetro a sé fa specchio: ed egli)

She, in the glass, he saw them in her eyes (Gli occhi di lei sereni a sé fa spegli).’

It is known that Rosalba owned a copy of the poem, and therefore the inspiration to create miniatures depicting the pair may have come from her reading of this. It is known that she read and translated Judith Drake’s Essay in Defence of the Female Sex (1696) into Italian, and was hence somewhat of an intellectual. Her sister, Giovanna, was listed by Luisa Bergalli in her 1726 anthology of women poets (the first of its kind to be published by a woman), as a poet herself. Therefore, the importance of poetry was not unknown to Carriera, and, as was, Oberer discusses, the saleability of erotic scenes such as this[8]. Along with her portraits of unknown peasant girls, scenes such as this were popular additions to snuffboxes, and remained so well into the nineteenth century. Carriera’s depictions, usually of women, were never as explicit as these scenes would later become, but were still taboo enough to be hidden from prying eyes by lids.

The back of this particular miniature is unfinished, leading to the suggestion that it was not intended to be part of a snuffbox. Instead, as was probably the case with the other miniature of this subject[9], this miniature may have been bought by a collector or Grand Tourist to display, in full view, in their home.

Fig. 6: ROSALBA CARRIERA (1675-1757), Portrait miniature of a lady in Venetian dress, c.1710-20, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, oval, 3 5/8 in. (94 mm) high, sold by The Limner Company.

The portrait of a lady in Venetian Dress (fig. 6) was discovered by the Limner Company in 2024, and is exemplary of Carriera’s talent in capturing the textures of fabrics and fashion from the Venetian settecento. It has already been mentioned that Carriera first trained in lacemaking, and her knowledge of the patterns and nature of this material is clear in the lace cuffs and stomacher worn by the unknown woman in this picture. She was able to achieve the texture she did by applying both light washes of watercolour and heavier patches of impasto, particularly visible in the green and pink fabric that makes up the woman’s dress.

Fig. 7: Detail from ROSALBA CARRIERA (1675-1757), Portrait miniature of a lady in Venetian dress, c.1710-20, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, oval, 3 5/8 in. (94 mm) high, sold by The Limner Company.

Her zendale, or the black silk and lace hood, dominates the portrait. These items of clothing were both important in the everyday life of Venetians, and, most significantly, were worn with masks during carnival. Combined with a mask, the hoods provided a disguise, and were worn by both men and women to hide not only their identity but possibly their gender. Another miniature showing a woman in the same type of hood in the Wallace Collection[10] indicates the popularity of these accessories, or perhaps that Carriera had one in her studio for sitters to wear, if they wished.

We do not know who this woman was, but if she was a visitor to the serenissima, it is possible that she asked Carriera specifically to paint her in this outfit, as a symbol to anyone who saw the miniature that she was well-travelled. There are other known examples of portraits by Carriera in which sitters are painted in particularly Venetian costume, including a pastel of Charles Sackville[11], and the portrait of Catherine Tofts, painted alongside Consul Joseph Smith (fig.7). Furthermore, A miniature featured in the 2023 exhibition at the Ca’Rezzonico features a Venetian noblewoman accosted by a figure also in a zendale and, in this case, a mask[12].

Fig. 8: ROSALBA CARRIERA (Venice 1673 - 1757), Portrait of Joseph Smith and Catherine Tofts as Thalia, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, oval, 3 3/8 x 4 1/2 in (8.5 x 11.5 cm), researched by Stephane Renard, Mrs. Bożena Anna Kowalczyk, attribution confirmed by Bernardina Sani.

A unique miniature in Carriera’s oeuvre is a double portrait of Consul Joseph Smith (1682-1770) and Catherine Tofts (ca. 1685 - 1756), in the guise of Thalia (fig. 8). This miniature was discovered and researched by Stephane Renard, with the help of Mrs. Bożena Anna Kowalczyk, and the attribution to Carriera has been confirmed by Bernardina Sani, and we are indebted to all three for the information we have on this miniature. It was possible to identify merchant-come-art collector-come-agent Joseph Smith from a comparison with a portrait by Giovanni Grevemboch (1731-1807)[13], and the identification of Tofts comes from the fact that the two were in a relationship when the miniature appears to have been painted, around 1715. The pair were married in 1717, and this portrait therefore documents the beginning of their love story. It has been suggested that Tofts is dressed as Thalia, the muse of comedy, because of the mask that she holds in her hand. It has also been suggested that the mask could be a hint towards the fact that Tofts moved to Venice to escape creditors- and that this is a disguise in order to hide from them. It also references her career as an opera singer, a career in which costume was often worn.

The sitters in this miniature are representative of Carriera’s network in Venice. Smith was an agent to her, and Canaletto, as well as a patron, as it is assumed that this portrait was painted for him personally. By developing connections with figures such as Smith and Cole, it is clear that Carriera was able to develop personally and financially. But, as the existence of this miniature also proves, she was willing to honour these friendships by producing wonderfully creative works of art, like this miniature, that would have been close to the heart of those depicted.

Fig. 8: ROSALBA CARRIERA (1673-1757), Portrait miniature of a Gentleman wearing armour breastplate and blue cloak, holding the Coronation Medal of George I, circa 1715, watercolour, bodycolour and gold paint on ivory, later silver-gilt frame with blue enamel border, oval, 75 mm. (2.9ins) wide, sold by The Limner Company.

Oberer (2023) has suggested that Carriera’s sittings with male clients would have been more heavily monitored than those with female clients[14], and this could be a reason for there being both fewer portraits of men by her, and the fact that these are, on the whole, less elaborate in their costume and scenery. The above portrait, also sold by the Limner Company, is another unique example from her oeuvre, in the fact that it does contain some more interesting details, largely in the object that the sitter holds. This is the Coronation medal of George I. Again, the sitter remains anonymous, but it is suggested that he was an English visitor to Venice on the Grand Tour and that he is holding the medal as a proud recipient. The miniature is also unique in its format- the horizontal oval is the same as that of the portrait of Smith and Tofts, but as far as the author has been able to find, this is the only example of a single male portrait in this format by Carriera.

Certainly, in comparison to some of her portrait miniatures of men, including that of an unknown man in the Metropolitan Museum (no. 49.122.2), and the portrait of Christoffel Bernhard Julius von Schwartz in the Rijksmuseum (SK-A-4032), this portrait has more depth and intrigue. It is also more unique in providing an object through which, at the time, this gentleman would be more easily identified. Other miniatures of gentlemen by Carriera have similar objects of intrigue, such as the snuff box held by the gentleman in her portrait identified as the Young Pretender[15], but these are nowhere near as common as they are in both miniatures and pastels depicting female sitters.

Carriera as a woman’s woman

To lead on from this note that Carriera’s portraits of women are on the whole more creative than those of men, it is important to discuss her attitude towards her own gender that became apparent throughout Carriera’s career. It has already been seen that Carriera was supported by multiple male figures in her art, but it is also clear that she was keen to help other, younger women develop their own skills and to become artists in their own right.

Rosalba and her sister Giovanna were two of only seven miniature painters in Venice, as recorded by Vicenzo Corelli in 1697. It is assumed that Giovanna was trained by her sister, and she was to become one of many women involved in Carriera’s studio. Her other students included Felicita Sartori (b.1713), and Marianna Carlevarijs (1703-1750), daughter of the famed view painter Luca. Her students were trained in both miniature and pastel, and it is tempting to think that Carriera purposefully employed women. Of course, their presence in the studio would have also been influenced by the assumption that miniature painting was a ‘feminine’ art. Furthermore, Carriera also had male students, including the aforementioned Felice Ramelli. Whether purposeful or not, her employment of these women did give them a step-up in their careers.

This sense that Carriera put more creative energy into painting women in outfits decorated with flowers and in allegorical guises goes hand in hand with the idea that she was a supporter of women, or a woman’s woman. As is demonstrated by her oeuvre, there were plenty of gentlemen willing to wear costumes. It was perhaps easier for Carriera to relate to, and feel a willingness to, paint portraits of women in these even when they were strangers, whereas she was only happy to do this for men if they were already friends.

The end of Carriera’s career

In the 1720s, Carriera’s focus moved more towards producing pastel portraits, and she produced fewer and fewer miniatures. By 1724, she had begun to experience issues with her vision, meaning it was almost impossible for her to work in this smaller medium. Health conditions like this were not uncommon amongst artists and miniaturists. She underwent two painful cataract surgeries in 1746 and 1751. Unfortunately, neither worked, and she died six years later. At this point, she had lost her sister, Giovanna and was being cared for by Angela. One testament to the success of her career at her death was the 24,556 Zecchini, including investments, that she left behind. This was significantly more money than the legacy of herher male counterparts[16].

Carriera’s footprint is certainly very clear in the history of miniature painting. For the following centuries, ivory remained the most popular support for these portraits, and their intimate and jewel-like nature continued to capture the hearts of sitters and recipients across the globe. Her works capture the intricate artistic networks of Settecento Venice, as well as providing an insight into the place women held as professional artists in the rococo period.

[1] This is said except for a select few publications, including the catalogue produced to accompany the Ca’Rezzonico’s exhibition ‘Rosalba Carriera: Miniature su Avorio’, held between October 2023 and January 2024, and curated by Alberto Craievich, and C J de Bruijn Kops’ 1988 article, published as part of the Bulletin of the Rijksmuseum.

[2] One of the most informative English-language works on Carriera’s life was written by Angela Oberer as part of the Illuminating Women Artists: The Eighteenth Century series. See A. Oberer, Rosalba Carriera, Los Angeles, Getty Publications, 2023.

[3] The Kunstsammlungen Dresden has one of the largest collections of works by Carriera,

[4] N. Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1900, online edition, ‘COLE, CHRISTIAN’.

[5] Many of the contemporary comments on her beauty are typically misogynistic for their time. Carriera was seen by others as a talented artist, though there was often a ‘but’ relating to her attractiveness linked to this, possibly linked to a sense that only a woman with male qualities could ever have as much talent as this.

[6] Still in the collection of the Accademia di San Luca, illustrated Sani, Rosalba Carriera, 2007, cat no. 16, p. 70.

[7] Quote from Francesco Stiparoli in 1715, cited by B. Falconi, ‘Rosalba Carriera e la miniatura su avorio’, in Rosalba Carriera, Convegno Internazionale di Studi, Venice, Fondazione Giorgio Cini; Chioggia, Auditorium San Nicolò, 26-28 April 2007.

[8] Oberer, 2023, p.29.

[9] Which is believed to have been brought back from Venice by Lord Burlington by 1715.

[10] Rosalba Carriera (1673 - 1757), An Unknown Lady in an Italian Dress, circa 1710-1720, Wallace Collection, London, collection no. M310.

[11] Sani, 2007, no. 321. At that point, this pastel was still in the collection of Lord Sackville, Sevenoaks, Kent.

[12] A. Craievich, Rosalba Carriera: Miniature su Avorio, Scripta, Venice, 2023, cat. no. 34. Private collection.

[13] GIOVANNI GREVEMBOCH, Portrait of Joseph Smith, 1754 - 1759. Pencil and watercolour on paper, 28x20 cm. Page from Gli abiti de' veneziani di quasi ogni età con diligenza raccolti e dipinti nel secolo XVIII, Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici Veneziani, Correr Museum Library, MS Gradenigo-Dolfin 49, II, fol. 125.2.

[14] Oberer, 2023, p.38.

[15]Based on the reproduction seen by the author, the gentleman in this portrait does not look like the Young Pretender. This miniature is in the Louvre, Department of Graphic art, RF30678.

[16] Oberer, 2023, pp.116-117.

19 Jan 2026

Burnsiana.

‘Fintry, my stay in worldly strife, Friend o’ my Muse, Friend o’ my Life’:

Portrait Miniatures of Robert Burns’s staunch friend and patron,

Robert Graham of Fintry (1749-1815), and two of his children.

No celebrant of Burns Night requires an introduction to Robert Graham of Fintry, the distinguished Angus laird whose lineage traces back to King Robert III.[1] Graham of Fintry was among the poet’s most steadfast and pragmatic patrons, a measured and perceptive correspondent, and, above all, the indispensable confidant who secured for Burns what he himself termed his “sheet anchor in life”, a job with the Scottish Excise.[2] The Grahams of Fintry have since been custodians of significant Burns manuscripts, many now housed in national institutions, including a copy of the celebrated Tam o’ Shanter (1790). Like the manuscripts, this refined group of late eighteenth-century portrait miniatures has descended through the Graham of Fintry lineage, emerging only recently from private hands. For admirers of Burns, these miniatures stand as rare and eloquent relics of the poet’s cultivated and expansive social milieu. They evoke a friendship rooted not only in shared virtues, such as industry, resilience, and conscientiousness, but also in a deep and abiding Scottish identity. Graham of Fintry has been described as ‘the best friend the Poet ever had.’[3] This article examines this famous friendship, the themes and motives that shaped it, and the context it provides for the commission of these three refined miniatures.

|

|

|

||

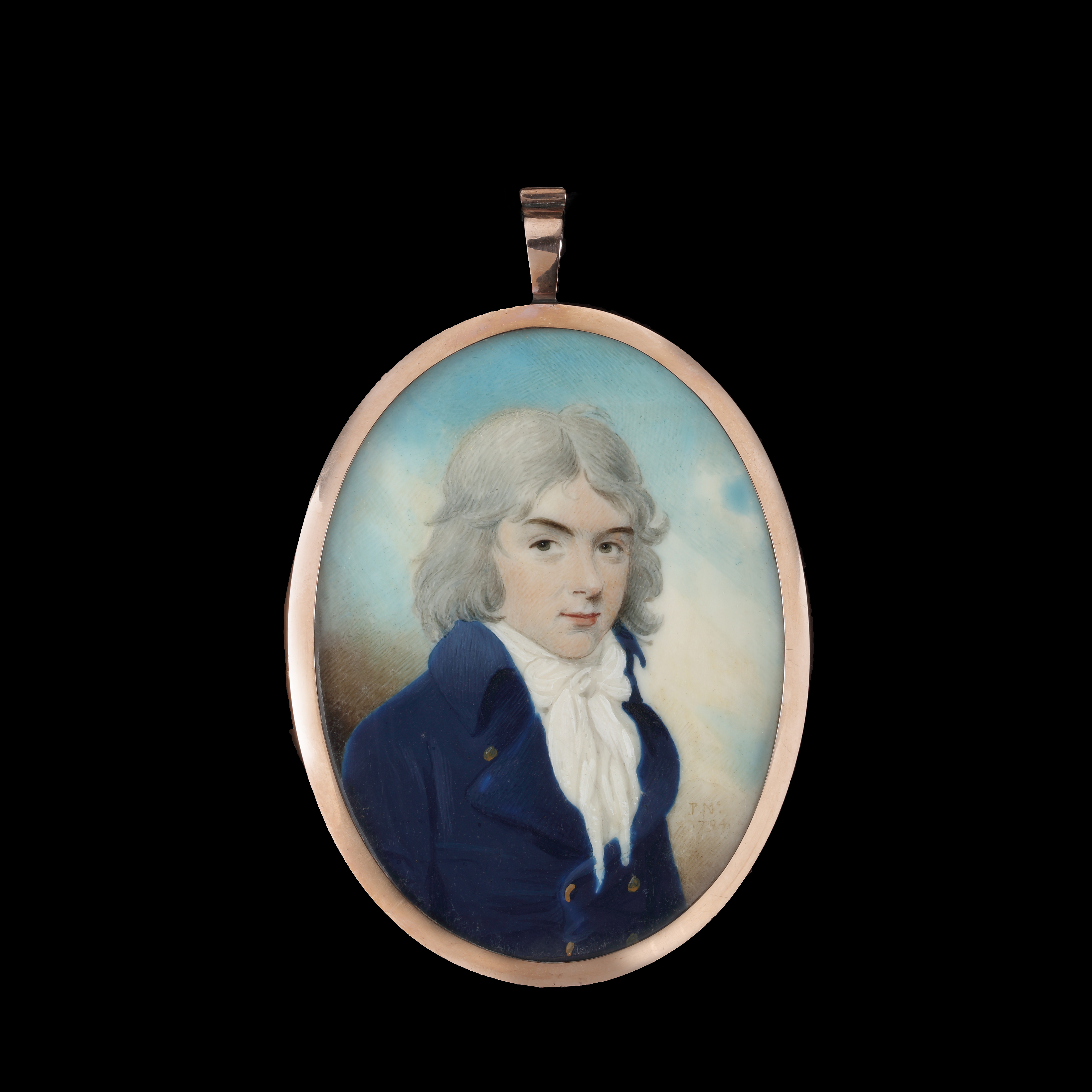

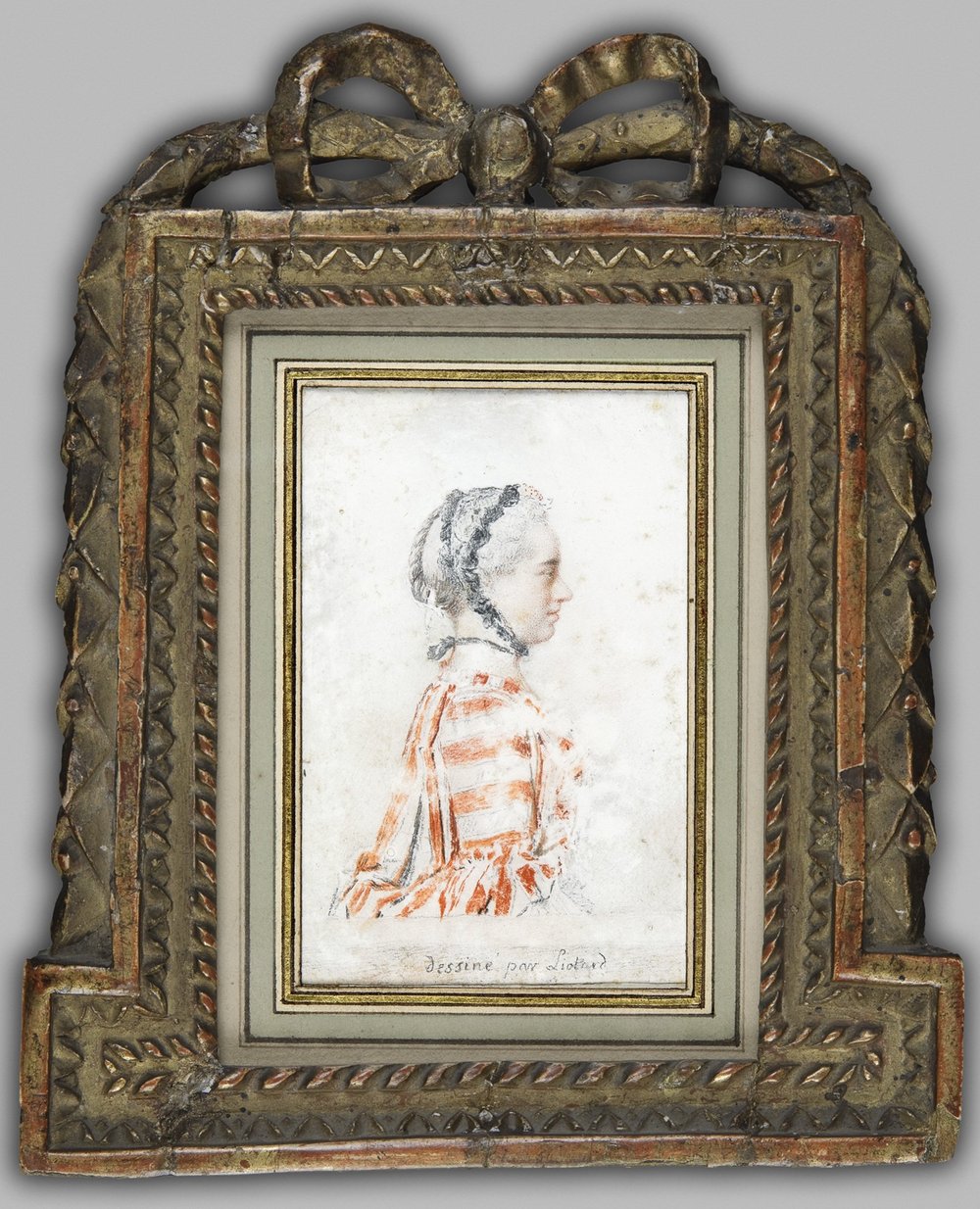

| Fig. 1. THOMAS HAZLEHURST (c.1740–c.1821), Portrait Miniature of Robert Graham of Fintry (1745-1819), 1793. The Limner Company. | |

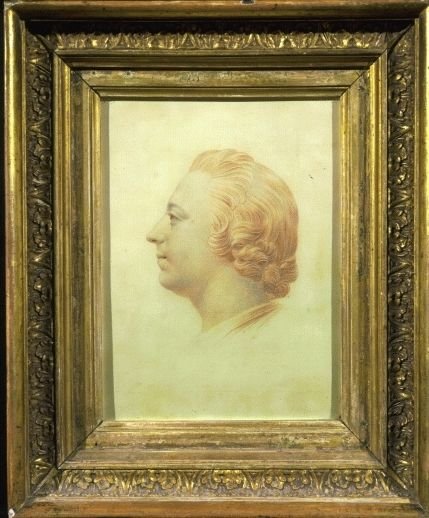

Fig. 2. ANDREW PLIMER (1763–1837), Portrait miniature of a daughter of Robert Graham of Fintry, circa 1798. The Limner Company. | |

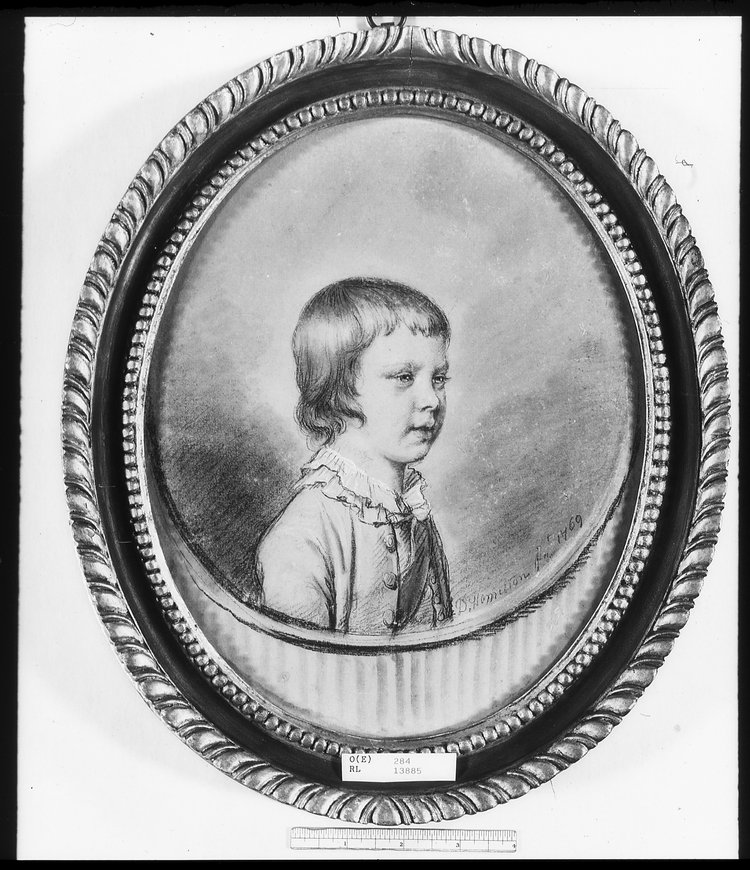

Fig. 3. PATRICK JOHN MCMORELAND (1741 -c.1809), Portrait miniature of a son of Robert Graham of Fintry, 1794. The Limner Company. |

1. Fintry: a brief biography (pre-1787)

2. How Fintry and Burns met

Fig. 2

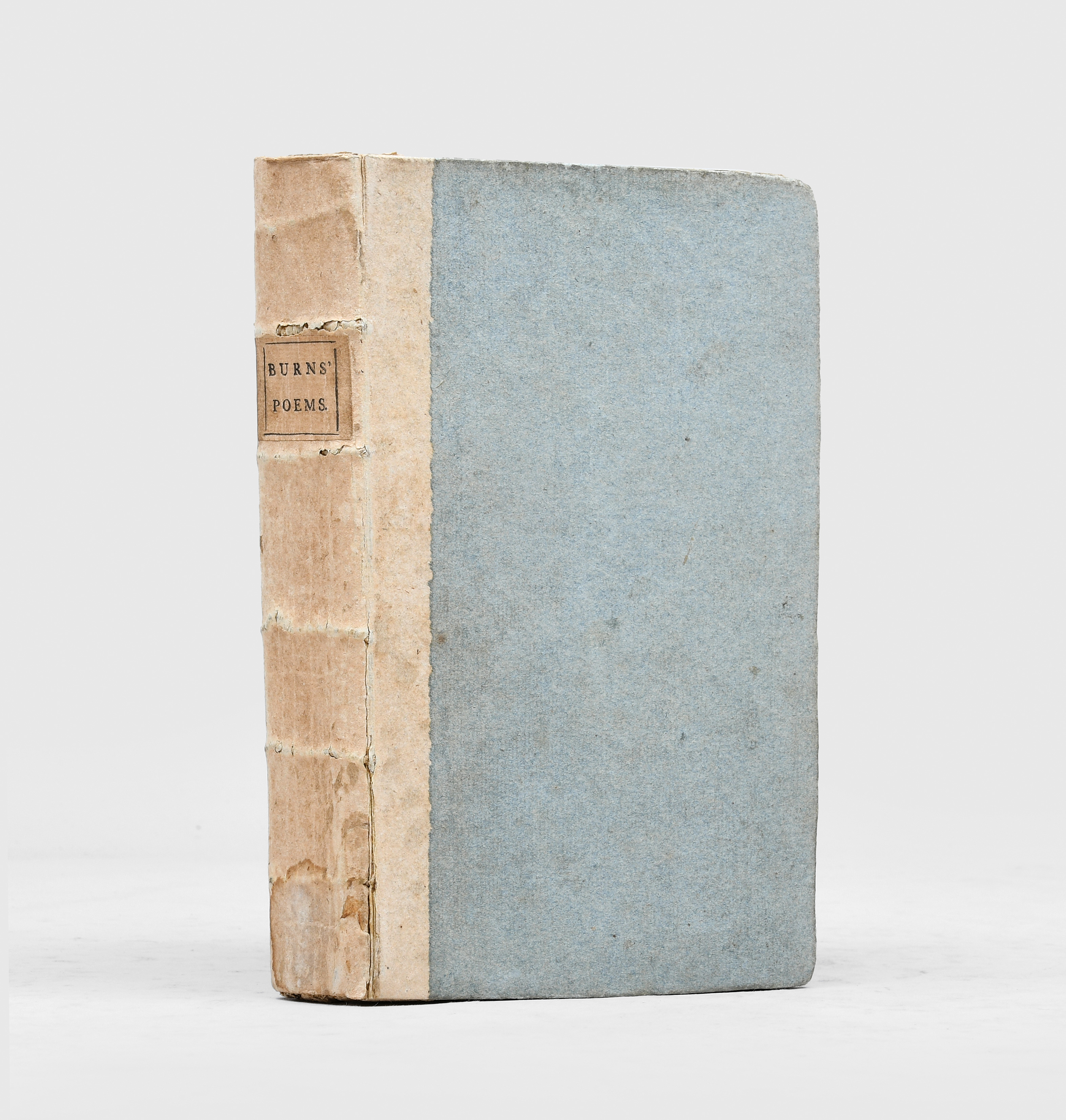

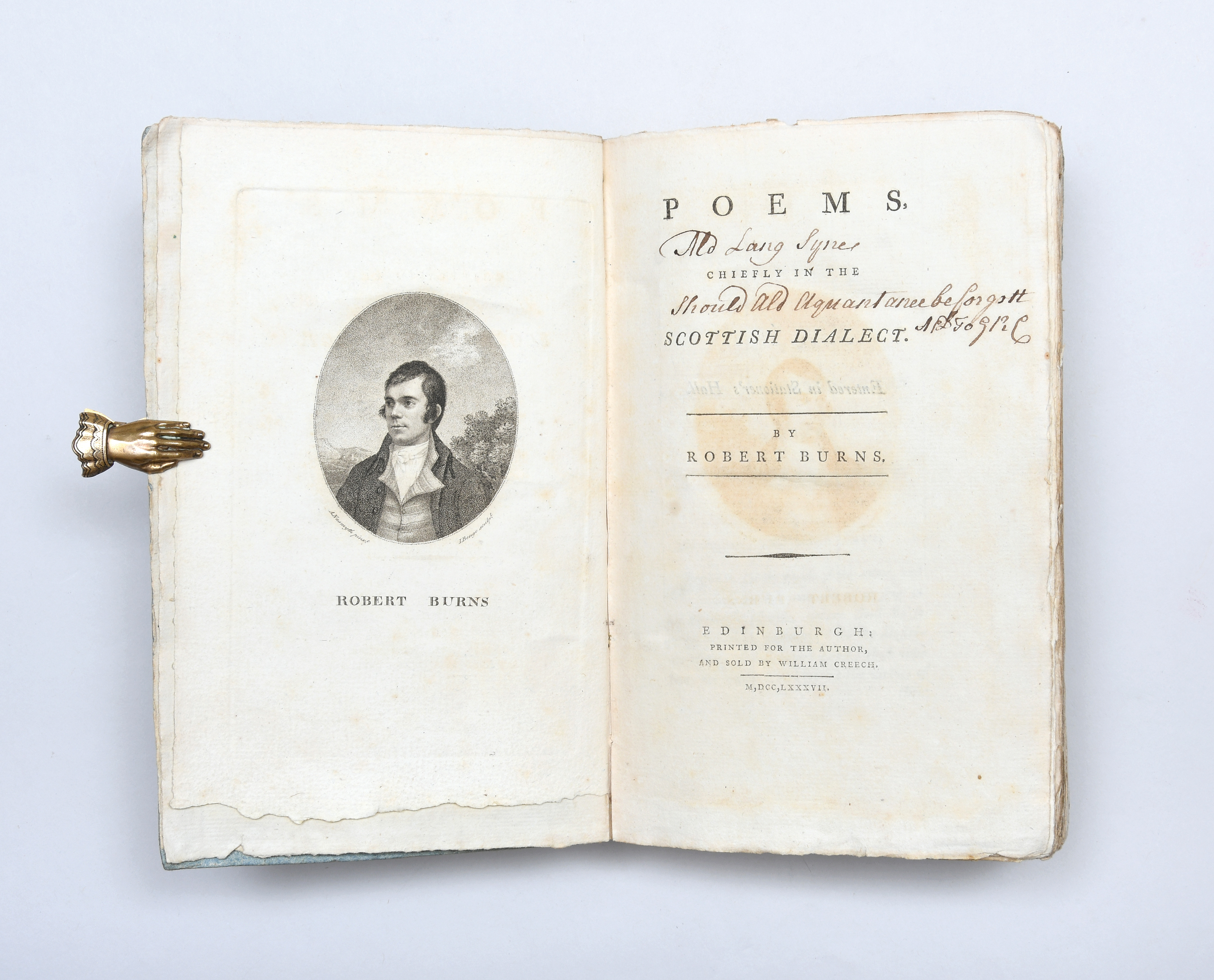

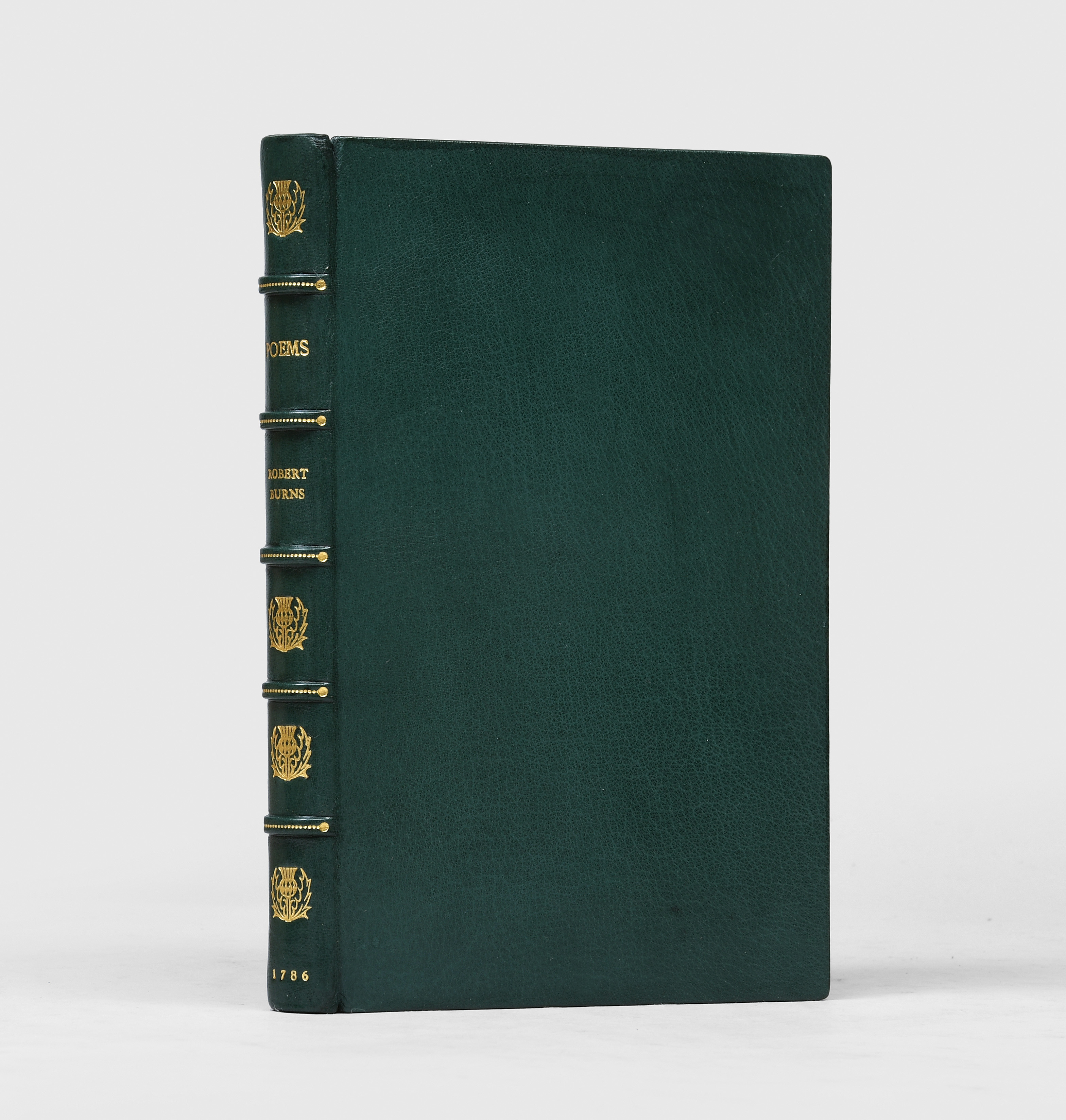

ROBERT BURNS (1759-1796), Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect

The Bradley Martin copy, in original boards

Edinburgh: Printed for the Author, 1787

Peter Harrington (Stock Code: 174292)

Fig. 3

ROBERT BURNS (1759-1796), Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect

Handsomely bound copy

Glasgow: John Smith & Son (Glasgow) Ltd, 1927

Peter Harrington (Stock Code: 161013)

3. Fintry’s Character

Contemporary accounts seem to portray Fintry as a lively, sociable figure with a distinct joie de vivre. He played golf and cricket, attended university balls, enjoyed convivial drinking, and like many gentlemen of his era, suffered intermittent attacks of gout.[15] He was also capable of dramatic action: on one occasion, he reportedly defended a property from a violent mob, an episode that brought him public commendation.[16] As to his temperament, the poetess Mary Eleanor Bowes called him “a man of violent resentments”, while another source styled him a ‘staunch churchman’ devoted to the Monifieth Parish Church.[17] Taken together, these glimpses suggest a worldly, resilient, occasionally peppery, but socially astute gentleman.

Fintry was very much a product of the Scottish Enlightenment, committed to the ideals of improvement and economic progress. He supported a range of developmental initiatives, including the repurposing of waste ground in Dundee and the establishment of the cotton-manufacturing village of Stanley near Perth. He contributed to the reform of canvas-manufacturing standards for maritime use,[18] and in 1795 he was appointed an office-bearer of The Society for the Improvement of British Wool.[19] Intellectually, he aligned himself with the ideas of Adam Smith, whose Wealth of Nations (1776) he later lent to Burns.

Although descended from Jacobite forebears,[20] Fintry’s own political loyalties were firmly pro-Hanoverian. Overall, he was ‘a dedicated Whig’ committed to moderate, constitutional politics.[21] Alongside the Duke of Atholl, he moved in the influential orbit of Henry Dundas (1742–1811), the powerful Scottish manager of Pitt’s administration. Dundas’s programme in Scotland centred on consolidating government influence among Highland elites, securing compliant parliamentary seats, and encouraging military recruitment by tapping into the Highlands’ martial traditions.[22] Fintry participated actively in these networks. He received payments from Dundas’s secret service fund for intelligence work that supported ministerial propaganda and countered radical agitation.[23] Following the French Revolution and the rise of republican unrest, he oversaw a group of paid informants monitoring radical activity in the Dundee area.[24] He also belonged to the Dundee Club, an organisation committed to curbing local expressions of ‘disloyalty and sedition’ against the British Constitution.[25]

Burns was not indifferent to the influence Fintry wielded. “Fortune, Sir, has made you powerful & me impotent; has given you patronage, & me dependence,” he remarked with characteristic frankness.[26] On another occasion, he acknowledged that he had found in “Mr. Graham a very powerful and kind friend.”[27] Yet Burns did not approach him as a superior. Rather, Fintry’s character intrigued him. He esteemed his intellect and considered him a man with whom he could converse as an equal in spirit. It is on these qualities that the tone of their surviving correspondence rests. To be sure, the correspondence is shaped by Burns’s petitions for assistance, but it is animated, too, by the mutual respect and curiosity that underpinned their relationship.

4. The Correspondence, the poems, the Excise

The tone of Burns’s letters to Fintry has often been described as “unscrupulous”:[32] forthright, pressing, and unapologetically candid. At times melodramatic but more often contrite, the correspondence reveals a writer acutely conscious of his precarious position. Burns constructs a persona at once humble and ambitious, a kind of penniless ‘apprentice’ whose gratitude can be extravagant, even theatrical, yet whose pride and determination ring unmistakably through the pleas. By contrast, Fintry emerges as patron and friend, but also as a ‘Master’, someone Burns admires and hopes to learn from.[33]

Burns’s first bold appeal for Fintry’s patronage came in January 1788. He had recently submitted his application to the Board of Excise and sought appointment as an Officer under Fintry’s protection.[34] In this letter, Burns, ‘the heaven-taught ploughman’, voiced his fear of remaining an unsuccessful ‘country farmer’ and of earning too little to support his family. Within two months he had secured an instructor, an Excise Officer in Ayrshire, and promptly asked Fintry to encourage the Excise Secretary to authorise this arrangement. Fintry acted without delay. In September 1788, Burns pressed further, expressing a desire to be placed in the Dumfries Excise Division, an outcome possible only if an existing officer were displaced. Burns’s urgent tone may have been because of his difficulties at Ellisland Farm. He had recently leased the place and worried that he would not be able to make it profitable. His anxieties assumed literary form when he wrote To Robert Graham, Esq., of Fintry, with a request for an Excise Division (1788), an Augustan compliment in the manner of Pope, where the poet clings to “generous Graham” like a vine seeking support.[35] The following spring and summer brought rising confidence. Between May and July 1789 Burns was discussing a role in the local Excise station with Collector John Mitchell, whom Fintry had introduced to him through a letter of recommendation. Burns’s gratitude took poetic form in To Robert Graham, Esq., of Fintry, on Receiving a Favour, a sonnet of August 1789. By December he reported that he had been training with Collector Mitchell and Supervisor Findlater and was at last serving as an Excise Officer on a ten-parish “ride” in Nithsdale. Burns’s progress was swift.

By the summer of 1790 he had obtained a foot-walk Division in Dumfries – the “tobacco district” – again through Mitchell’s assistance.[36] As the burdens of Ellisland grew intolerable, he confided to Fintry his wish to focus wholly on the Excise, with hopes of eventual promotion to Examiner or a post in a Port Division. Yet 1790 also brought political daring. After the burgh elections, Burns sent Fintry an audacious poetic commentary: the Epistle to Robert Graham of Fintry on the Election for the Dumfries String of Boroughs (1790). Here he denounced the Duke of Queensberry’s hypocrisy and mocked the corruption of the electoral system in tones reminiscent of Pope and Hogarth.[37] The following year, having resolved to abandon the farm and move his family to Dumfries, Burns returned to the poetic mode of petition in To Robert Graham of Fintry, Esq. (1791). Written after the death of his earlier patron Glencairn, the poem is a lament in which the poet, weakened, overburdened, and impoverished, turns to Fintry for compassion and support. Critics have often judged the ‘Fintry poems’ as histrionic or sycophantic, but this final piece is widely regarded as the finest. Burns adopts the persona of the reckless poet who, purely driven by poetic inspiration, unleashes his voice to tell uncomfortable truths about Scotland’s political integrity and the decay of its aristocracy, and to educate his patron about the difficulties of a poetic existence.[38]

The most intense phase of their correspondence came with the political storm of late 1792. In December, Burns wrote to Fintry in alarm: Collector Mitchell had received an order from the Excise Board to investigate accusations that Burns was “a person disaffected to Government.” Burns suspected betrayal by someone who knew him well. He was so desperate to save his reputation that he invoked Fintry’s marriage and fatherhood. Fintry’s reply was reportedly reassuring, though he required Burns to answer each charge. Burns’s response, written in January 1793, stretched to seven pages. He denied involvement with any Republican group in Dumfries, and denied the rumour that he had joined a crowd singing the French revolutionary anthem Ça ira in defiance of the King and the Constitution. He also denied any association with Captain Johnson, publisher of the radical Edinburgh Gazetteer. Critics have often found Burns’s defence thin and unconvincing,[39] yet its conclusion is astonishing: after addressing every allegation, Burns renewed his request for Fintry’s help in obtaining a Supervisor’s post, a promotion that, as events would prove, never came.

5. An analysis of Fintry’s patronage

Fintry’s affinity for Burns can be partly explained by his own familiarity with instability and the uncertainties of fortune. He was a seasoned Scotsman who understood the contradictions of human nature and the precariousness of economic life. Although he had not experienced rural poverty firsthand, he had managed estates, dealt with tenants, and participated in agricultural improvement. These experiences gave him insight into the vulnerabilities of farming life. Burns expressed his fear of financial collapse – a fear sharpened by the memory of his father’s ruin and the lawsuit that followed – to Fintry at least once: “I have lived to see repeatedly throw a venerable Parent in the jaws of a Jail; where, but for the Poor Man’s last and often best friend, Death, he might have ended his days.”[40] Fintry, too, had lost his father very young, a trauma that may have shaped the difficulties he later faced in sustaining the family estate. After their fathers’ deaths, both he and Burns found themselves responsible for supporting their families, Burns as a tenant farmer, Fintry as a factor. It is no surprise, then, that Burns appealed to him in terms he knew would resonate: “Sir, you are a Husband & a father… you know what you would feel to see the much-loved wife of your bosom & your helpless prattling little ones, turned adrift into the world.”[41] Burns’s strategic invocation of shared anxieties about domestic responsibility reveals acute sensitivity to Fintry’s own emotional landscape.

Burns also understood how to appeal to other aspects of Fintry’s character. His letters, often signed with declarations of “native gratitude,” tapped into a shared sense of patriotism and civic purpose.[42] Politically, the two men were not so far apart. Both were patriotic Scots employed by the British state; both worked as ‘gaugers’, positions that attracted resentment from segments of society, but offered routes to influence and advancement. Fintry’s commitment to economic improvement and national progress aligned with Burns’s own hopes for reform. Indeed, in his letter of January 1793, Burns openly professed his adherence to the “Reform Principles”: “I look upon the British Constitution, as settled at the Revolution, to be the most glorious Constitution on earth, or that perhaps the wit of man can frame; at the same time, I think, & you know what High and distinguished Characters have for some time thought so, that we have a good deal deviated from the original principles of that Constitution […]”.[43] Burns clearly believed that Fintry would understand, and perhaps share, similar feelings about the current state of corruption. He would not have risked such a statement had he not been confident of Fintry’s sympathetic ear.

Meanwhile, Fintry was not oblivious to Burns’s radicalism.[44] Fintry showed great humanity during the episode of Ça ira at the theatre, which should be seen in the context of the growing number of radical riots and new radical society spreading in the manufacturing regions of lowland Scotland after the French Revolution (1792-94). The elite, to which Fintry belonged, grew concerned and sent letters to the government about these activities. Henry Dundas was convinced insurrection was imminent in Scotland and intensified his measures to spy on dissidents and radicals. As mentioned before, Fintry was one of these government informers.[45] He was paying spies to detect radical activity in the Dundee area. According to Scott Hogg, this is something that would have shocked Burns, and it points to the possibility of Fintry’s disloyalty towards him.[46] Though participating in this repressive climate, Fintry was simply committed to the order and stability of Dundee.[47] He was powerful, but he was still a local official. He was, perhaps, glad that he was not obliged to watch radical societies in Dumfries and he could assure Burns that he was safe, and no proceedings would be brought against him. According to Noble and Scott Hogg, Fintry was ‘keeping [Burns] dependent and cornered in Dumfries. Burns himself, of course, was desperate to have the Excise move him to the more radically sympathetic West Scotland’. [48] Ultimately, what counts is that Fintry did not expose his Bard friend.

Burns himself recognised the depth of Fintry’s support. Writing to Professor Stewart, he affirmed his “doubly indebted” gratitude for acts of kindness “done in a manner grateful to the delicate feelings of sensibility.”[49] To Fintry he wrote: “You, Sir, have patronized and befriended me… by being my persevering Friend in real life.”[50] Burns understood precisely which of Fintry’s qualities – his benevolence, his sense of duty, his personal experience of loss – were most likely to secure his sympathy, and he used them with remarkable dexterity. Yet this dynamic cannot be characterised as one-sided. Burns offered something tangible in return. His poems, circulated in manuscript among Edinburgh’s intellectual elite, brought Fintry’s name into influential literary networks; his printed dedication publicly associated Fintry with the cultural prestige of Scotland’s most celebrated poet; and his correspondence consistently cast Fintry as a man of discernment, benevolence, and refined judgement.

Seen in this light, their relationship was not merely a pattern of petition and patronage but a reciprocal exchange. Burns secured stability and protection during his most vulnerable years, while Fintry acquired cultural visibility and a lasting association with the emerging national bard. This mutual convenience—reinforced by genuine respect and shared convictions—helps explain why Fintry remained one of Burns’s most consistent and loyal supporters during the most precarious period of the poet’s life.

6. Fintry’s fame

Burns’s literary output played a significant, though often overlooked, role in shaping Fintry’s public image. His first poem for Fintry, composed in September 1788, remained unpublished but circulated widely in manuscript among influential figures, including Professor Dugald Stewart and Henry Erskine.[51] Of the four poems addressed to Fintry, only To Robert Graham of Fintry, Esq. (1791) appeared in print during Burns’s lifetime, included in the Second Edinburgh Edition of 1793.[52] However, its insight into the Poet’s precarious position was so compelling that Samuel Taylor Coleridge later transcribed two of its stanzas in a private letter.[53] This circulation – both of manuscript and printed material – placed Fintry’s name in the hands of Scotland’s intellectual elite and associated him with one of the era’s most celebrated literary voices. It is therefore reasonable to argue that Burns enhanced Fintry’s cultural profile, situating him within a wider literary and intellectual milieu that extended far beyond his administrative sphere. Viewed in this light, the resurfaced miniatures can be read not merely as family heirlooms but as material witnesses to a reciprocal relationship in which patronage, reputation, and artistic production were mutually reinforcing. In particular, the portrait miniature of Fintry discussed below, painted in the same year as the Second Edinburgh Edition, appears to reflect his desire to present himself as a sensitive man of culture and intellectual standing.

7. The Portrait Miniatures

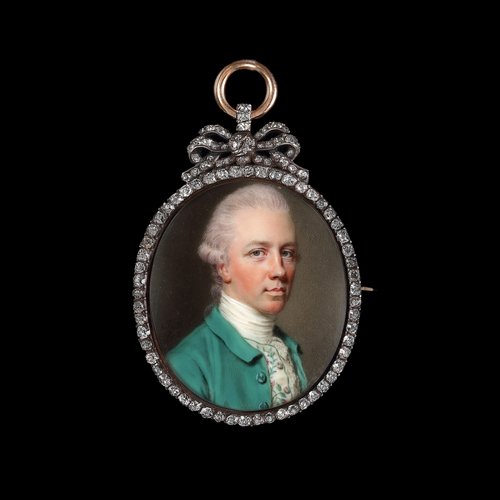

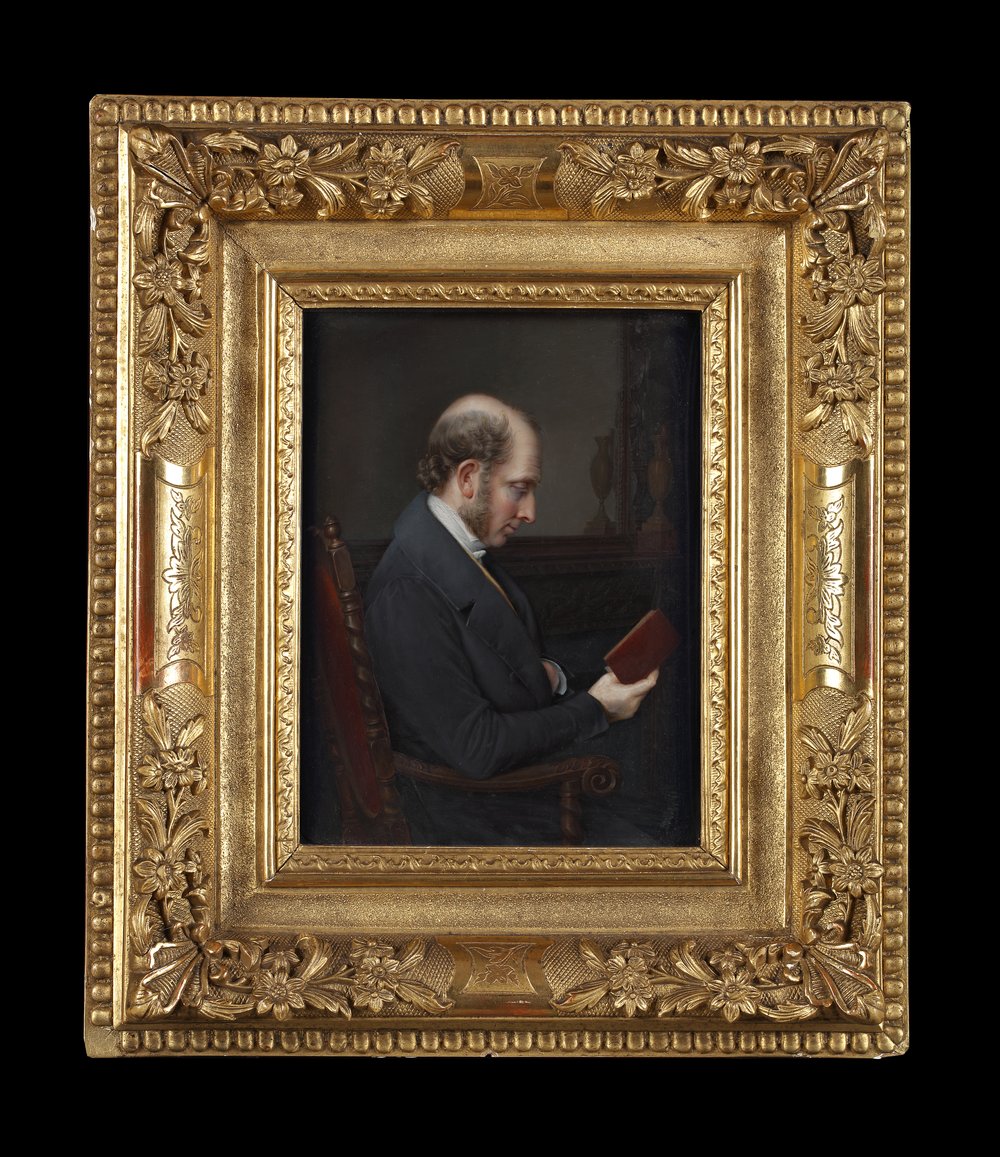

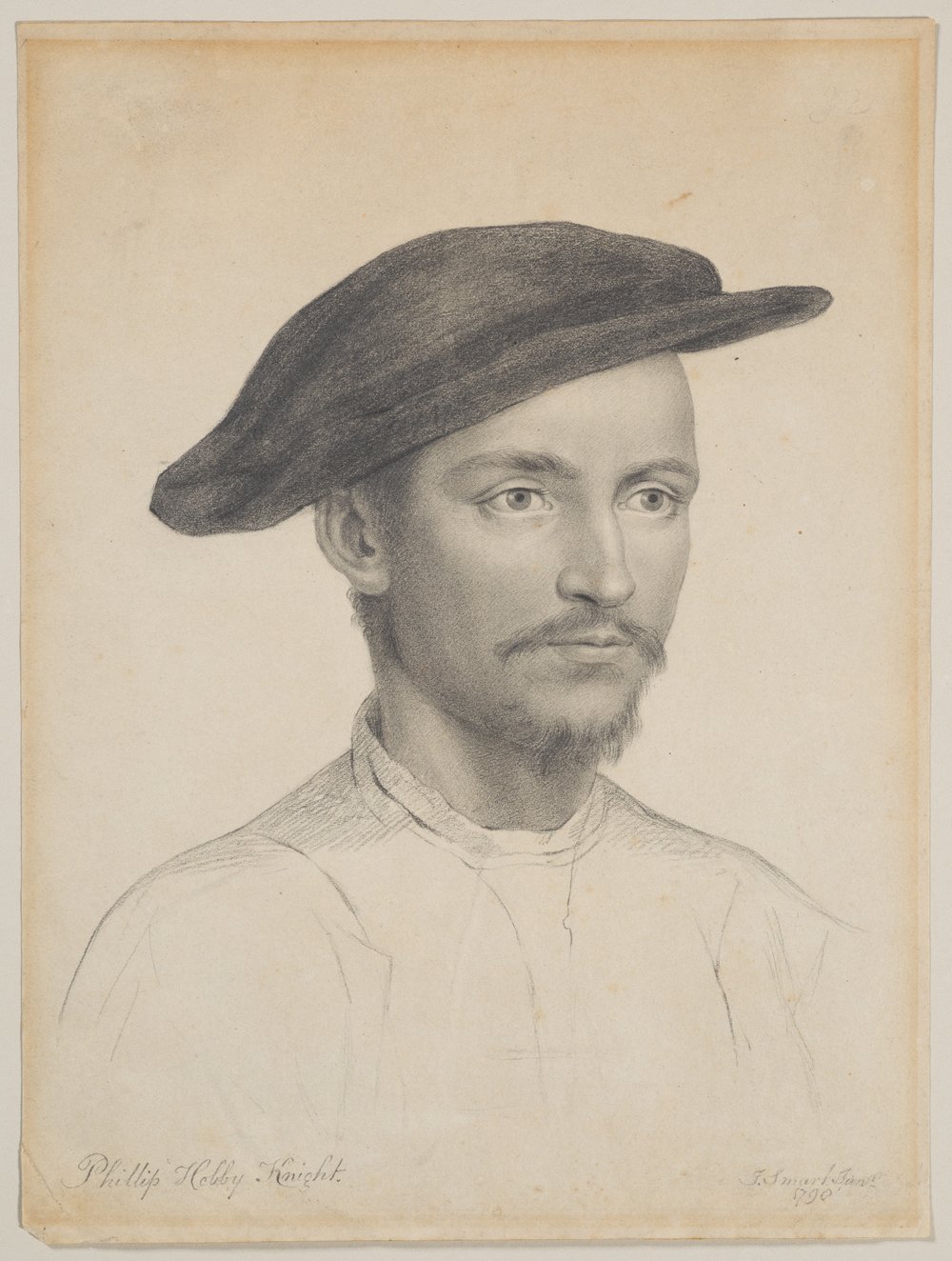

The exquisite, finely finished portrait of Robert Graham of Fintry is signed with the crisp Roman initials “T·H” and dated at the lower left. It was painted in 1793 by the Liverpool-based miniaturist Thomas Hazelhurst (c.1740–c.1821), then working from 9 Rodney Street.[55] The portrait belongs to a pivotal moment in the Burns-Fintry friendship when Fintry was helping the poet defend himself against charges of disloyalty, and when To Robert Graham of Fintry, Esq. appeared in the Second Edinburgh Edition. It was also the year Fintry received payment for disseminating pro–William Pitt propaganda, and his son John had just been commissioned as an Ensign in the 85th Regiment of Foot.[56] The miniature displays several hallmarks of Hazelhurst’s hand, including the bluish shading of the face and the subtle halo of lighter background framing the sitter.[57] Looked at closely, this portrait is astonishing in the way it combines the many facets of Fintry’s personality. He appears as a man of the Establishment, wearing a powdered wig en queue and a dark blue coat. Yet he is shown facing left, a pose that softens formality and offers the viewer a glimpse of a more expressive, emotional temperament.[58] This impression is heightened by the delicate white highlights on the eyes, which animate the sitter with lifelike immediacy and suggest the innate goodness Burns had so recently proclaimed to the world. Moreover, his white cravat, tied in the fashion of a blooming flower, may be read as symbolic of intellectual refinement, openness of character, and emotional sensitivity – all qualities we have pointed out in this article.

The second miniature is almost certainly a portrait of Robert (1775–1799), Fintry’s eldest son. Painted in 1794 by Patrick John McMorland (1741–c.1809), the work depicts the young sitter in a navy coat and white cravat, his powdered hair worn loose and flowing, set against a blue-sky background with foliage to the left. Although McMorland’s style exhibited considerable range, the handling of this piece closely recalls two gentlemen’s miniatures he produced in the mid- to late 1790s during his Manchester period, suggesting a consistent approach to male portraiture in these years.[59] The miniature bears on its verso two interlaced initials, ‘RG’ and ‘DG’. The slightly smaller ‘DG’ may plausibly refer to David Graham, a younger brother of the sitter, who was only nine years old when Robert departed for India and to whom the miniature may have been entrusted as a personal token. The miniature was very likely conceived as a parting gift, commissioned on the occasion of Robert’s appointment to the East India Company as Second Assistant Register at the Provincial Court of Appeal and Court of Circuit in the Province of Benares.[60] His promising career was cut tragically short: Robert was killed in the Massacre of Benares, murdered on the orders of the ex-Nawab of Awadh, Wazir Ali Khan, in retaliation against the British Bengal Establishment.[61] Among the few personal possessions he carried to India was “A Portrait Miniature Set in Gold,” evidently preserved as a cherished keepsake from the Fintry household.[62]

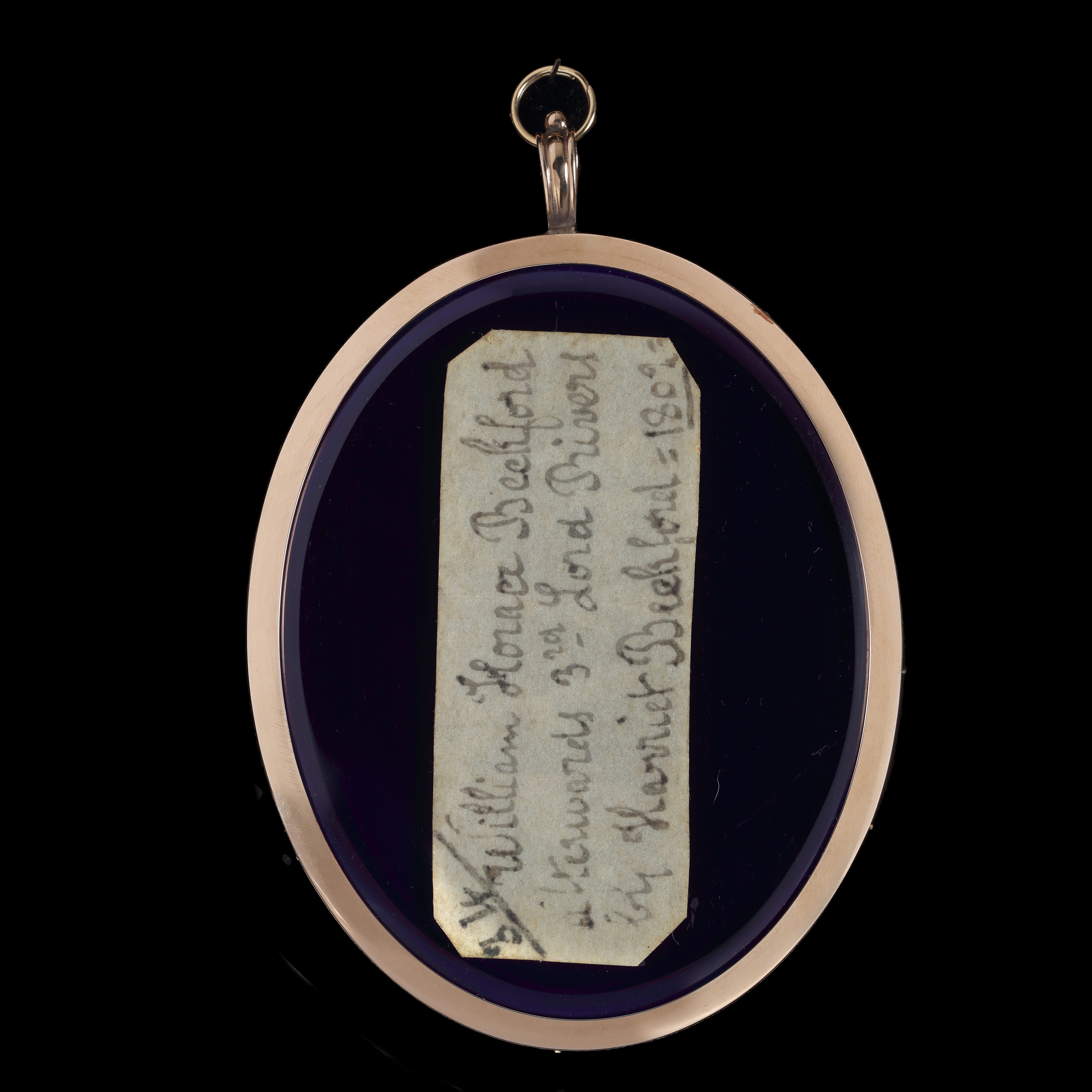

The third miniature is a finely executed and delicately observed portrait of one of Robert Graham’s elder daughters, most probably Anne. Painted around 1798 by Andrew Plimer (1763–1837), it dates from the period when Plimer, formerly apprenticed to Richard Cosway, had established his own successful practice in fashionable Golden Square, London. It was in these years, more than two decades before his later tours of Scotland, that he produced the portrait of ‘Miss Graham’. The work displays several hallmarks of Plimer’s mature manner. Most notable is the characteristic cross-hatching visible in the background on either side of the sitter, a technique through which he created depth and tonal nuance by means of fine, intersecting strokes. The absence of a signature is consistent with Plimer’s so-called “second phase” (after 1789), when he frequently left his miniatures unsigned.[63] The qualities singled out by George C. Williamson as emblematic of Plimer’s style – his distinctive handling of hair and the luminous brilliance of the eye – are both clearly present here.[64] It is striking that the locks of auburn hair set into the reverse of the miniature match the sitter’s hair precisely, suggesting not only that the portrait has retained its original vividness, but also that the material fragment reinforces the miniature’s claim to authenticity and intimacy. In a similarly delicate way, Anne Graham was the recipient of Burns’s To Miss Graham of Fintry, a formal sonnet composed in Dumfries in January 1794.[65] Burns later sent her a copy of A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs, inscribing it with the opening line of the poem: “Here, where the Scottish Muse immortal lives.” In his final letter to Fintry, Burns explained that this gift to Anne was intended as a gesture of gratitude to his patron and the Graham family.[66]

8. Brief conclusion

[1] The branch of the Grahams of Fintry traces their descent from Sir William, Lord of Grahame and his second wife, Princess Mary Stewart, daughter of Robert III (c.1337-1406). See S.C. Lomas, The Manuscripts in the Possession of Sir John James Graham of Fintry K.C.M.G., in Historical Manuscript Commission (1909). Report on Manuscripts in Various Collections, vol. V. Hereford: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, p. 185.

[2] ‘Your Honorable Board, sometime ago, gave me my Excise Commission; which I regard as my sheet anchor in life’. The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 425.

[3] James Cameron Ewing and Andrew Mac Callum, ‘Robert Graham Twelfth of Fintry’, in The Burns Chronicles, 1931, p. 35.

[4] Fintry’s children were: Isabella-Gray (1774-1774); Robert (1775-1799); Isabella (1776-1854); Colonel John Graham (1778-1822); Margaret (1780-1798); Thomas (1781-1822); Mrs Anne Brodrick (1783-1852); David (1785-1824); Elizabeth-Kinlock (1789-1789); Mrs Elizabeth Keay (1791-1873); Mrs Helen-Christian Cloete (1792-1870); Mrs Jemima Agnes Dundas (1793-1874); Emily Georgina (1795-1881); James-Scott (1796-1804); Mary-Cathcart (1796-1854); Catherine-Margaret (1799-1876); Roberta (1801-1868); and the last daughter, Mrs Caroline MacKay Carr (1802-1837).

[5] https://drive.google.com/file/d/1T0fvDKE-jbfsH3WvJoYO3kgwUSk_0oMV/view

[6]London Gazette, 20 January 1787, p. 2.

[7] J.C. Ewing (1927). Journal of a Tour in the Highlands made in the year 1787 by Robert Burns. London: Gowans & Gray, pp. 13-14.

[8] In his Journal, Burns frequently refers with nostalgia to the events of the 1715 and 1745 Jacobite uprisings and the Battle of Culloden (1746). See Nigel Leask ed. (2014) The Oxford Edition of the Works of Robert Burns, p. 140.

[9] The Grahams of Fintry maintained a long-established feudal relationship with the Duke of Atholl, involving the payment of rents, feu duties, keeping of accounts, and various other obligations. On the death of Fintry’s father, his estates included: “The forest or glen of Binachrombie or Glenmore ‘disposed’ to the said Robert Graham by James, Duke of Atholl, and redeemable by him’. Also, Fintry’s father took a job as a factor and general forester to the Second Duke of Atholl. Fintry’s brother, Captain James Graham, was an officer of the 77th Atholl Highlanders Regiment.

See S.C. Lomas, The Manuscripts in the Possession of Sir John James Graham of Fintry K.C.M.G., in Historical Manuscript Commission (1909). Report on Manuscripts in Various Collections, vol. V. Hereford: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, p. 222; and Robert Francis Mudie, and David Morrison Walker (1964). Mains Castle & the Grahams of Fintry. Dundee: Abertay Historical Society Publication no.9, p. 16; https://deriv.nls.uk/dcn23/9519/95199077.23.pdf.

[10] The introduction to the duke came from Professor Hugh Blair of Edinburgh. Hogg, p. 161. His Ayrshire friend, Rev. Josiah Walker, tutor to the Duke’s son, later said of Burns’ visit to Blair Atholl, that it was ‘ability alone that gave him a title to be there’. Scott Douglas, vol. I, p. 367. See The Canongate Burns, p. 281.

[11] Letter to Josiah Walker, 5 September 1787. Maurice Lindsay (1970). The Burns Encyclopedia. London: Hutchinson, p.149.

[12] Ian McIntyre (1995), Robert Burns A Life, p.162.

[13] Letter to Mrs Dunlop, 10 December 1788.

[14] Letter to Dr Moore, 4 January 1789.

[15] MUDIE, Robert Francis, Sir, K.C.S.I..; WALKER, David Morrison (1964) Mains Castle & the Grahams of Fintry. Dundee: Abertay Historical Society Publication no.9, p.17; S.C. Lomas, The Manuscripts in the Possession of Sir John James Graham of Fintry K.C.M.G., in Historical Manuscript Commission (1909). Report on Manuscripts in Various Collections, vol. V. Hereford: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, p. 269.

[16] James Cameron Ewing and Andrew Mac Callum, ‘Robert Graham Twelfth of Fintry’, in The Burns Chronicles, 1931, pp. 42-43.

[17] Broughty Ferry Guide and Advertiser, 6 February 1954, p. 6.

[18] https://drive.google.com/file/d/1T0fvDKE-jbfsH3WvJoYO3kgwUSk_0oMV/view

[19] Oracle, 19 February 1795, p. 3.

[20] Graham John Graham of Cleverhouse, the Jacobite general who died at Killiecrankie in 1689.

[21] Nigel Leask ed. (2014). The Oxford Edition of the Works of Robert Burns, p. 141.

[22] Dundas, too, like Burns, was traversing the Highlands at the end of the summer of 1787. Yet despite their shared routes and mutual connections, Burns and Dundas did not meet at that time. Nigel Leask, ‘My Heart’s in the Highlands’, in Gerard Carruthers, ed. (2024). The Oxford Handbook of Robert Burns, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 32-33.

[23] The Canongate Burns, p. 251; and Patrick Scott Hogg (2008), pp. 19 and 252.

[24] Bob Harris (2005). The Scottish People and the French Revolution. London: Pickering & Chatto, p. 118.

[25] True Briton, 16 February 1793, p. 1.

[26] The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 436.

[27] Letter from Robert Burns to Robert Graham, 9 December 1789.

[28] The Canongate Burns, p. 697; Scott Hogg, p. 196.

[29] The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 428.

[30] Both Allan Cunningham, Burns' 19th-century editor, and Rev. George Gilfillan claimed Burns visited Fintry’s home. Also, Margaret Hutchinson apparently met the poet at the house of Fintry in Dundee. Fife Herald, 20 May 1880, p. 3. See also Dundee Evening Telegraph, 23 January 1902, p. 3; and Broughty Ferry Guide and Advertiser, 6 February 1954, p. 6.

[31] In May 1789, Burns mentioned preparing a manuscript book of his unpublished poems for Mrs Graham. He also sent her a copy of Lament of Mary Queen of Scots on the Approach of Spring (1790) and a copy of The Rights of Women (1792). He later composed a sonnet in honour of Miss Graham (1794), which was first printed in 1800. The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 428; The Canongate Burns, pp. 246 and 809.

[32] Maurice Lindsay (1970), p. 149.

[33] ‘When Lear, in Shakespeare, asks old Kent why he wished to be in his service, he answers, “Because you have that in your face I could like to call Master’”. The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 424.

[34] To be considered for the post, a candidate had to be between 21 and 30 years of age; if married, he should not have more than two children; he had to understand the basics of arithmetic; and he had to be a member of the Church of England; he had to provide the names of two securities to answer to £200 for the execution of his office. Ian McIntyre (1995), Robert Burns A Life, p.191.

[35] The Canongate Burns, pp. 694-98.

[36] Burns was assigned the largest station within the Dumfries district, covering 10 parishes and one ‘ride’ each working day of the week, which included visits to ’21 spirit-dealers, 27 tobacconists, 2 tanners, 15 tea-dealers and 11 maltsters’. See Ian McIntyre (1995), Robert Burns A Life, pp. 260 and 279.

[37] The Canongate Burns, pp. 735-43.

[38] The Canongate Burns, pp. 249 and 719.

[39] Ian McIntyre (1995), Robert Burns A Life, p. 329-332.

[40] The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 424.

[41] The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 435.

[42] The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 425.

[43] The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 437.

[44] https://cdn.prgloo.com/media/9801e6a32164488bb46920d66d381377

[45] The Canongate Burns, p. 251; Liam McIllvanney (2002). Burns The Radical. Poetry and Politics in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland. Tuckwell Press, p.206.

[46] Patrick Scott Hogg (2008), p. 252.

[47] Harris, p. 3.

[48] The Canongate Burns, p. 251.

[49] Letter from Robert Burns to Professor Dugald Stewart, 20th January 1789.

[50] The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 425.

[51] Maurice Lindsay (1970), p. 150.

[52] The Canongate Burns, p. 246.

[53] The Canongate Burns, pp. 247 and 254.

[54] Heinz Archives, Notes on Collections, ‘Graham of Fintry’, p. 1.

[55] Daphne Foskett (1963) British Portrait Miniatures. London: Methuen, p. 146.

[56] Heinz Archives, Notes on Collections, ‘Graham of Fintry’, p. 2.

[57] Daphne Foskett (1963) British Portrait Miniatures. London: Methuen, p. 146; and Daphne Foskett (1972) A Dictionary of British Miniature Painters, vol. I. London: Faber & Faber, p. 319.

[58] Annukka K. Lindell (2025). ‘Turning the other cheek: Portraits of doctors and scientists don’t show a left-cheek bias’ in BCMJ, vol. 67, No. 2, available at: https://bcmj.org/articles/turning-other-cheek-portraits-doctors-and-scientists-dont-show-left-cheek-bias#:~:text=Research%20confirms%20that%20left%2Dcheek,judged%20to%20be%20more%20scientific.

[59] Heinz Archives, British Miniaturists 1775-1800 box, Patrick John McMorland file. See also Basil S. Long (1929). British Miniaturists. London: Geoffrey Bles, p. 285.

[60] Calcutta Gazette, 23 July 1795, p. 1.

[61] As a consequence of his unprincely behaviour, the British deposed Wazir Ali Khan (1780-1817) as Nawab of Awadh. Robert Graham was instructed to investigate the pretensions of the rival princes. When Wazir was replaced by Saadat Ali Khan II and asked to move to Calcutta, he organised a bloody insurrection and killed five officials, including Robert. Belfast News-Letter, 16 July 1799, p. 4.

[62] British Library, British India Office Inventories and Accounts of Deceased Estate (available in FindMyPast).

[63] Daphne Foskett (1972) A Dictionary of British Miniature Painters, vol. I. London: Faber & Faber, pp. 450-51.

[64] George C. Williamson (1897). Portrait Miniatures from the Time of Holbein 1531 to that of Sir William Ross 1860. A Handbook for Collectors. London: George Bell, p. 76.

[65] The Canongate Burns, pp. 809-10.

[66] The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 440.

[67] Letter from Robert Burns to Robert Graham of Fintry, Ellisland, 31st July 1789. In The Complete Letters of Robert Burns, p. 429.

19 Jan 2026

‘A force of expression quite out of the ordinary’; A rare portrait miniature by Ismael ‘Israel’ Mengs, Saxon Court Painter (1688-1764)

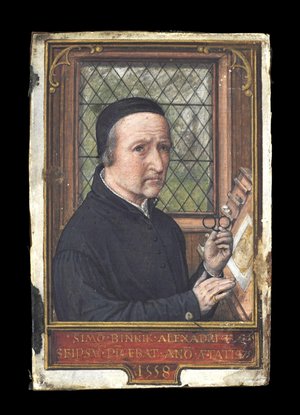

Fig. 1

Ismael Mengs, Self-portrait, watercolour and bodycolour on vellum, signed and dated 1711 (now lost),

reproduced from black and white photograph in Schidlof, ‘The Miniature in Europe’, 1964, pl. 812.

Fig. 2

Ismael Mengs, self-portrait in Polish Costume, circa 1714

Watercolour on parchment

Dimensions 9.3 x 7.4 cm

Now lost, this 1711 self-portrait, painted as a miniature on vellum, probably travelled with the young artist to showcase his skills. Originally from Lusatia – a region split between Poland and Germany - its companion piece was likely this rare character portrait – also known as a tronie[1] - of an elderly man wearing a fur hat. Also dated 1711, this portrait would have had the ability to convey that Mengs could take portraits from the life (as in his own self-portrait) but also the character studies required for history paintings. Another rare survival of a sketch by Mengs, also of an elderly man, is in the collection of the Albertina, Vienna (fig.4). As Andrea Lutz observes ‘Their closeness to reality and immediacy are of almost timeless validity, which makes the virtuously painted faces seem appealing and topical even today.’[2]

Fig. 3

Ismael Mengs, An Old man wearing a fur-trimmed hat, signed and dated 1711

Watercolour and bodycolour on vellum

The Limner Company

Fig 4.

Head of an Old Man

Drawing on paper

7,8 x 9,4 cm

Albertina, Vienna

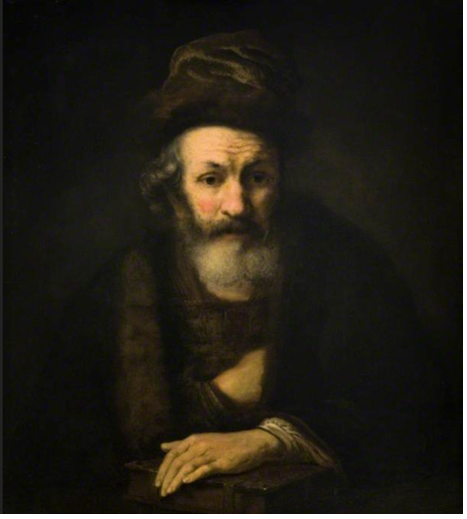

The image of this old man recalls the work of artists such as Rembrandt (1606-1669), who enjoyed painting tronies in the early to mid-17th century. Such studies allowed a degree of freedom on the part of the artist – a way to experiment with facial expressions which went beyond the stillness of a commissioned portrait. There was also freedom in the costume – with fantastical and eclectic dress from the artist’s imagination shown in such works. While they were often used for study and employed as practice during an artist’s apprenticeship, they were also created as independent works for the art market. By 1711, this type of artwork was beginning to go out of fashion. Here, Mengs looks back, possibly to the work of both Anthony and Abraham van Dyck (1599-1641) and (1635/6-1672) respectively. Particularly close are Anthony van Dyck’s tronies of men with beards and Abraham’s painting of ‘A Bearded Man in a Fur Hat with a Book’ (Burrell Collection).

Fig. 5

Abraham van Dyck (c.1635–1672) (attributed to), A Bearded Man in a Fur Hat with a Book

The Burrell Collection

Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Portrait of Painter Martin Ryckaert (1587-1631)

Prado, Madrid

Ismael was a fascinating character – he was a rebel, who lived outside societal norms. He changed his religion as often as he moved from country to country and yet he has been eclipsed by his son.

His longstanding affair with his housekeeper, Christiana Charlotta Bornmannin (1703-1731), produced four children, but the couple did not marry until near the end of her life in 1729. This unconventional relationship caused many issues, including the status of these illegitimate children. Whenever Christiana was pregnant, her and Ismael rented a house in Ústí nad Labem, Mírové Square, where they stayed until his wife gave birth. When the time came, Ismael Mengs visited the mayor, gave him a gift for the city’s needs, and requesting that he became the godfather of his children. He confirmed that they were born within marriage and were properly baptized in the Roman Catholic faith at the church in Ústí nad Labem. However, even the artist’s religion is still a matter of debate – long known as a Jewish artist, he became a Lutheran around 1710. Philipp Weilbach, in the Encyclopaedia of Danish artists stated that his ancestors had emigrated to Denmark from the Lausitz, Germany. Whether Ismael's parents had already embraced the Protestant religion, or whether the son took that step, had never been determined.

Ismael’s artistic career was long and varied but produced relatively little. Initially, he trained where he was born in Copenhagen – as a pupil of B. Coiffre – before moving to Lübeck. Around the time this portrait miniature was painted, he was in Hamburg, moving in 1713 to the court of Mecklenburg (where the future Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, would be born in 1744). He travelled widely during these years – moving to both Dresden and Leipzig and visiting Italy. Before his court appointment in Dresden, he likely painted another self-portrait on parchment showing himself in the typical dress of a Polish nobleman (complete with heron feathers in his hat). Able to work in enamel – as well as painting portrait miniatures on vellum and ivory – he was useful as a court artist. Portraits of Augustus II, the Strong (1670-1733) (he would show his strength by bending horseshoes and tossing foxes), Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, made in enamel, were part of his output.[3] A group of religious miniatures painted on ivory and in enamel also exist, probably conceived as a set, in the Dresden Gemäldegalerie. Nothing, however, seems to have surpassed his 1711 self-portrait, described by Schidlof as having ‘a force of expression quite out of the ordinary’ and the small tronie painted in the same year.

Fig. 7

Anton Raphael Mengs (1728–1779), Self-Portrait at Twelve Years Old, 1740

Black and red chalk

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 2464

After working for some time at the court of Augustus III, Ismael turned to teaching at the Academy in Dresden where he became director. This led him to the most important role of his career – as the tutor for his son, Anton Raphael (1728-1779), now thought of the as the preeminent artist of the Neoclassical period. Named after two of his father’s favourite artists (Anton for Antonio Allegri, better known as Correggio), Anton Raphael later noted his father’s strict upbringing and tyrannical training regime. Interestingly, Ismael taught his son through the copying of portraits by Anthony van Dyck, who his considered to be one of the greatest artists who had ever lived. In the mid 1750s, when Anton was at the height of his fame, to paint a portrait in the manner of van Dyck was considered a testament to an artist’s ability – judging from the existence of this small tronie, which is certainly painted with van Dyck in mind, little had changed in terms of admiration for this artist from the previous generation. Like his father, Anton also lived an unconventional life, marrying a girl who sat for him as a model called Margarita Guazzi, with whom he had twenty children and becoming friends with the notorious libertine Giacomo Casanova.

The emergence of the rare portrait miniature of an old man by Ismael Mengs comes at a time when his son’s work is undergoing review – with a comprehensive, monographic exhibition at the Prado in Madrid.

[1] The word ‘tronie’ is Dutch for ‘face’.

[2] Lutz on the exhibition ‘Portrait Tales – Portrait and Tronie in Dutch Art’. Exhibition: 11 March - 5 November 2023, Kunst Museum Winterthur, Switzerland.

[3] One enamel version exists in the Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Dresden, and another is noted in the Louvre, Paris by Schidlof.

04 Dec 2025

The Limner Company's Christmas Gift List

Miniatures have become a fashionable inspiration amongst contemporary artists in numerous media, and we’ve included many pieces belonging to this trend, alongside a selection of miniatures which are currently available on our website. As a theme, many of these could be gifted not only as works of art in their own right, but as items that could be worn, just as many miniatures would have originally been intended to be.

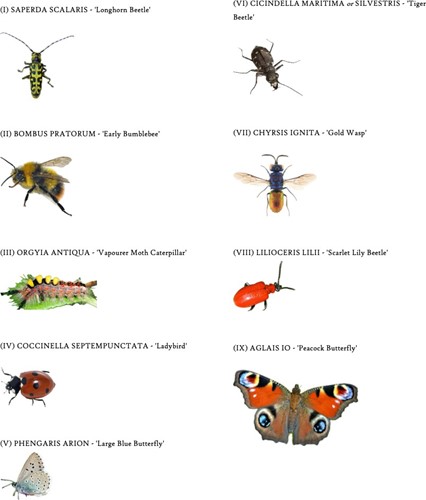

Figure 1- Rachel Larkins, Memento Mori Earrings, 2025, brass, resin, hand painted inserts, freshwater pearls, oxidised silver hooks, sold out, other pieces available via the Scottish Gallery’s website.

Rachel Larkins (b.1974) works from a studio near the New Forest and creates beautiful pieces of jewellery inspired by miniatures, memorial jewellery, and folklore. Some of her pieces, including some beautiful rings and earrings, are available through the Scottish Gallery website, where she is exhibiting until 23 December 2025. These earrings (sold out) reminded us of a pair of William and Mary memorial miniatures recently sold by the Limner Company…

Figure 2- ENGLISH SCHOOL, Memorial portrait miniatures of Queen Mary II (1662-1694) and King William III (1650-1702), circa 1702, watercolour on vellum. With the Limner Company, (reserved).

These memorial miniatures are a perfect example of how small and intimate these works of art can be. Painted following the death of King William III (1650-1702) and Queen Mary II (1662-1694), these tiny (16mm high) portraits (reserved) are both surmounted by loops which would have allowed them to be worn on a chain or ribbon by those mourning the death of the King and Queen. This has always been a common way to wear miniatures, as demonstrated in figure 3 below. It is tempting to envision the pair mounted as a brilliant pair of statement earrings to be worn today.

Figure 3- An image of a woman wearing a miniature on a ribbon, taken for the 2024 exhibition The Reflected Self, Compton Verney.

Figure 4- Holly Frean, A Pack of Kings and Queens, gouache on paper, sold out, other works available through her website.

William and Mary also feature in a work on paper by Holly Frean, A Pack of Kings and Queens (sold out). Given that early miniatures were painted on vellum, then laid down on playing cards, this artwork felt like the ideal addition to a miniatures themed christmas list. Holly, a london-based artist, has previously offered miniature pet portraits by commission (also currently sold out, for more information visit her website).

Figure 5- CONTINENTAL SCHOOL, c.1610s, Portrait of a Young Boy, oil on copper, heightened with gold. For sale with The Limner Company (£25,000).

If you’re looking for a historical miniature laid on a playing card, this Portrait of a Young Boy in a Lilac Doublet (£25,000) may be what you’re looking for. As shown here, he’s the perfect size to be worn as a pendant. Children were very rarely painted at the beginning of the seventeenth century, making this portrait an extremely precious and unique work. The reverse of the miniatures frame is transparent, revealing a single club on the playing card on which the vellum has been laid.

Figure 6- RICHARD COSWAY(1742-1821), Portrait miniature of a Lady, c.1770

watercolour on ivory. For sale with The Limner Company (£3,250).

If you know someone who prefers pink to purple, this portrait miniature of a lady by Richard Cosway should be on your list. She’s adorned with pink silk bows and delicate lace with pink embroidery, which Cosway has depicted falling down from her hair (£3,250).

This dress-up paper doll of Mrs Jervis, sold by Dennis Severs’ house, complete with a Spitalfields dress for her to wear (£12), could be the perfect stocking filler (featuring stockings) for any young aspiring fashion designers or historical fashion lovers! Dennis Severs bought the house in Spitalfields in 1979, and today, it is open to the public as a record of the Huguenot family who had lived there since 1874. If you know someone who would enjoy visiting the house, which was bought by Dennis Severs in 1979 and turned into a museum dedicated to recording the lives of a Huguenot family who had lived there since 1874, it is also possible to buy guided tours as gifts through the Museum’s website (from £16 per guest).

Figure 8- RICHARD CROSSE (1742-1810), Portrait of a gentleman in military-style dress, c. 1770, watercolour on ivory. For sale with The Limner Company (£2,250).

Turning to men’s fashion, this portrait of an unidentified gentleman by Richard Crosse features beautifully rendered fabrics, and is available on the Limner Company’s website (£2,250). On first glance he appears to be wearing military uniform (for some gifts for those who enjoy this, see below), but is in fact wearing an elaborate decorated jacket and waistcoat underneath which has been designed purely for fashion. He’s housed in a wonderful beaded frame, with a watch top- meaning he could easily be attached to a ribbon or chain and worn, as demonstrated with another miniature below…

Figure 9- An image of a lady wearing a miniature round her wrist, and a gentleman holding a miniature attached to a chain, taken for the 2024 exhibition The Reflected Self, Compton Verney

For those who enjoy military history more than fashion history, these handmade felt decorations of figures including Wellington, sold at the National Army Museum (£16.50), could be another great option for a stocking, or for a tree. Many museums and galleries sell similar felt decoration inspired by historical figures and artists. See the National Portrait Gallery’s website for more options, including the Six Wives of Henry VIII and Ignatius Sancho (from £17).

Figure 11- GEORGE ENGLEHEART (1750-1829), portrait of an officer, c.1790, watercolour on ivory. For sale with The Limner Company (£6,500).

Another option for a military history lover, which can double-up as a wearable piece, is this portrait miniature of an unknown officer by George Engleheart (£6,500). The miniature is set into a bracelet clasp, with a pearl surround, ready to be worn on someone’s wrist. The sitter is unidentified and may also prove a welcome mystery to a military buff- though his uniform appears to be that of a subaltern of a British Line Infantry regiment, his buttons may feature anchors, leading to the suggestion that he may have been a subaltern of the Corps of Marines…

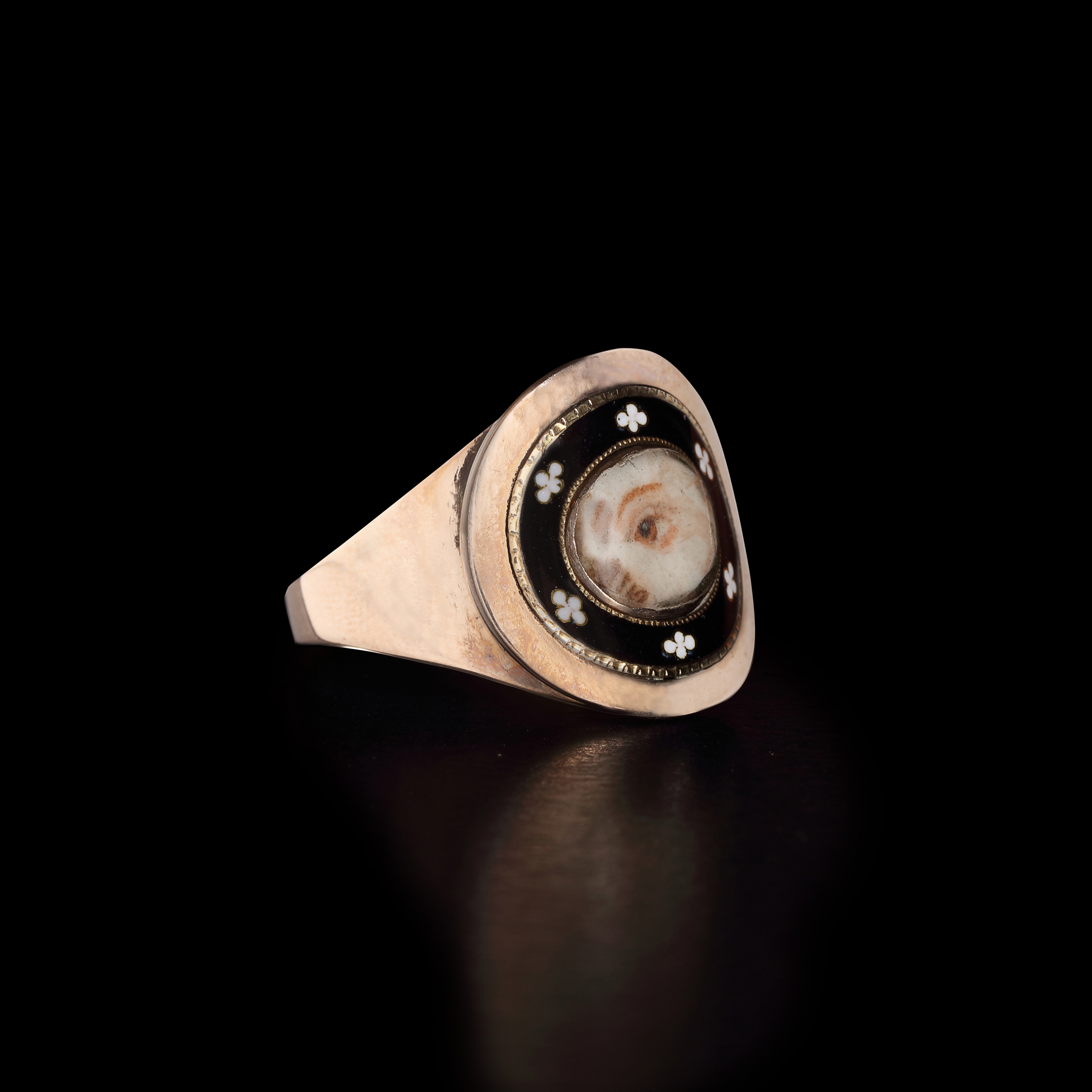

Figure 12- ENGLISH SCHOOL, A portrait miniature ‘lovers eye’ of the hazel eye of Ellen Jane, 1821, watercolour on ivory. With The Limner Company, (reserved).

Rings were also a traditional way to wear miniatures. Most often, portraits set into rings were intended as mourning jewellery, as with this ‘Lovers Eye’ mourning ring, featuring the eye of a young woman named ‘Ellen Jane’ (Reserved). It is possible to identify this as a mourning ring because of the black-and-white enamel surround; the white four-leaf clovers, specifically, would have conveyed the message to ‘think of me’.

Figure 13- Susannah Carson, No. 2988 Lover's Eye Painting on a Flow Blue Crescent Plate, china displayed on blue ironstone plate, £302, available through her website.

Susannah Carson puts a modern twist on the Lover’s eye in her artworks, through which she creates ceramic pieces featuring original eye paintings. Often selling out quickly, her plates and ornaments (such as the blue crescent plate above, £302) would be the perfect addition to a Christmas tablescape. At a lower price point, Susannah's Christmas shop contains eye miniature jigsaws (£25), stockings (£14), and wrapping paper (£11).

Figure 14- FRENCH SCHOOL (18th century), A double-sided hairwork miniature, c. 1780s, Hairwork on ivory (£1,750) and Marbled Case, produced by Parvum Opus (£350). Both for sale with The Limner Company.