By Guest blogger, Phoebe Griffiths |

30 Jun 2025

‘He calls her Dido’; Admiral Sir John Lindsay (1737-1788) and Dido Elizabeth Belle (1761-1804)

Figure 1. JOHN SMART (1741-1811) Portrait miniature of Admiral Sir John Lindsay (1737-1788), in gold-bordered naval uniform with gold buttons, white facings, white waistcoat and cravat, wearing the breast-star and red sash of the Order of Bath, powdered hair en queue; 1787 - for sale with The Limner Company

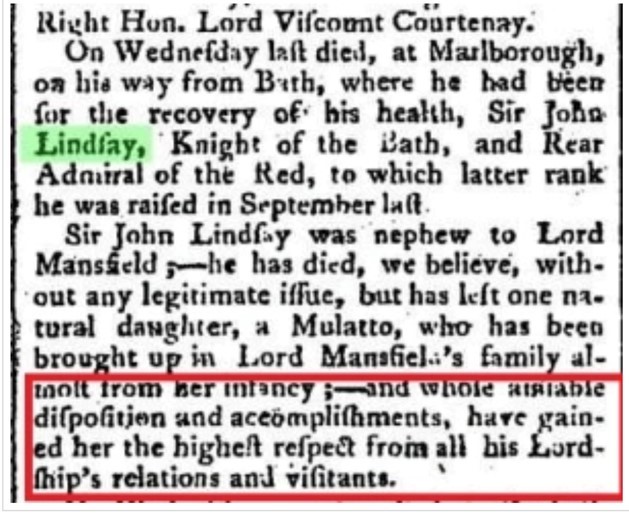

This, however, was not one of Smart’s usual commissions. For a start, the sitter was nowhere near India at the time. The subject of the portrait, Admiral Sir John Lindsay (1737-1788), shown here as a decorated and member of His Majesty’s Royal Navy, was in fact in England, where he was resting from an illness from which he was never to recover (he died the following year, aged only 51, in Marlborough whilst returning from Bath). Lindsay’s long naval career was detailed in his obituaries, with the London Chronicle also noting that he was the father of a woman whose ‘amiable disposition and accomplishments have gained her the highest respect from all his Lordship’s relations and visitants’.[1] This young woman was Dido Elizabeth Belle, her name taken from her mother, Maria Bell(e), a West Indian enslaved woman.

Dido’s story has been romanticised, glamourised and even televised (in the 2013 film ‘Belle’).[2] In a portrait of the late 1770s by David Martin (1737-1797) [fig.2], she is shown on apparently equal footing with her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray (1760-1825).[3] Here, unlike most other contemporary portraits, we see an affectionate interracial relationship, in contrast to the servant-master bond traditionally portrayed. However, Dido’s origins were far-removed from this idyll in which she frolics. We do not know the circumstances under which she was conceived, but in 1760, when Lindsay was in his early 20s, he brought to England a woman who had been taken prisoner onboard a Spanish vessel, pregnant with his child.[4]

Figure 2. DAVID MARTIN (1737-1797) double portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray at Kenwood House, c.1776 - Earl of Mansfield, Scone Palace, Perth, Scotland

Mother and child lived together in London until a plan was formed in which Dido would move to Kenwood House, to live with Lord and Lady Mansfield, the uncle and aunt of her father. By this time, Lindsay was knighted and, when Dido was around five years of age, he set sail again, this time posted to Pensacola, Florida as captain of HMS Tartar. It was whilst he was there, on the 20th December 1765, that he purchased or acquired two adjacent parcels of land, jointly given the number 6 – one part was to build a house upon, the other to be used as an orchard/garden.

Sir John returned to London in 1767. During his absence, his daughter Dido was baptised on the 20th November 1766, aged five. The baptism took place in Bloomsbury, with her mother being simply named as Maria, wife of ‘Mr Bell’. Seven years later, Maria left London as her daughter moved to Kenwood to begin her education and introduction into society. At this point, Maria, who was officially owned by Lindsay, was formally freed – with the transfer of land to her name stating ‘a negro woman of Pensacola in America, but now of London, aforesaid made free of the other part’.

Dido’s story, and that of her parents, plays out against the background of her great-uncle’s William Murray’s famous case of ‘Somerset v Stewart’. Murray, now Lord Mansfield, was an experienced judge when the case was brought before him at the Court of the King’s Bench in 1772. The case verdict was seen as a landmark judgement on the legal status of slavery in England. His final ruling established that slavery was unsupported by English common law and that an enslaved person could not be forcibly removed from England and sent to Jamaica for sale. This monumental decision had far-reaching effects on the abolitionist movement, the transatlantic slave trade, and the legal status of slavery in the British Empire and beyond.

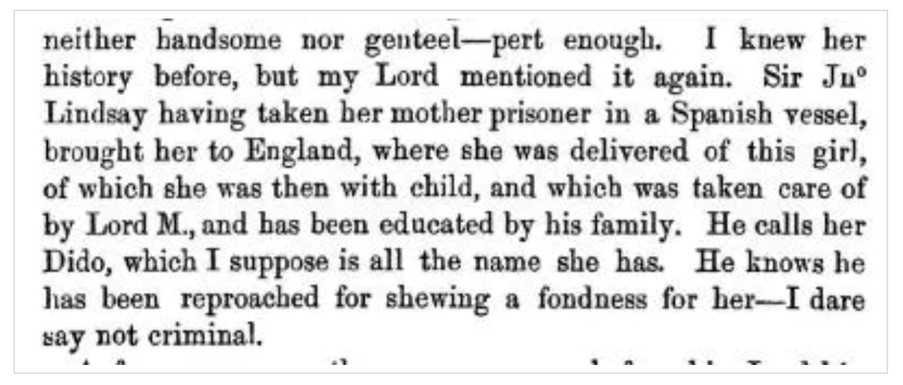

Figure 3. The diary and letters of His Excellency Thomas Hutchinson, p.276.

Figure 3. The diary and letters of His Excellency Thomas Hutchinson, p.276.We have no account of Lindsay’s relationship with his eldest daughter, other than Thomas Hutchinson’s diary which states that he had been shamed for the ‘fondness’ that he had shown his daughter [fig.3]. It is not possible to know if this was because ‘fondness’ was frowned upon generally at this time in parent/child relationships or whether this was a comment on her mother’s status as a slave. Either way, he was not named nor was he present at her baptism. We cannot know if Dido’s invitation to live at Kenwood was instigated by her father, as he moved her mother to another continent. In 1768, John Lindsay married Mary Milner, but the couple had no children. Despite having fathered five children with different women in Jamaica between 1761-1767, Lindsay appears to have been faithful once married.

Figure 4. Public Advertiser, 10 June 1788.

In a final act, perhaps in acknowledgment of a daughter of whom he was proud, John was instrumental in naming a new ship HMS Dido, in the month of her 21st birthday. Whilst Sir John returned from his command in late October 1784, he would have heard of the launching of HMS Dido on the 27th November 1784. On the 24th September 1787, the same year that this portrait was painted by John Smart, HMS Dido was commissioned by the Royal Navy for service. That very day, Sir John was promoted by the king to Rear Admiral of the Red – the highest promotion for a rear admiral. Although Lindsay and Smart were thousands of miles apart, it is possible that, having met each other in 1781, Smart was the only artist trusted to paint a miniature of the Rear Admiral – but who was it for? As Lindsay’s wife Mary did not die until 1799, it was quite possibly commissioned by her – but Dido is another possibility as the recipient – as is so often the case, we can only speculate…

[1] London Chronicle, 7 June 1788. Quoted in Byrne, p.210.

[2] After the film came out, Paula Byrne wrote a book the following year entitled ‘Belle: The True Story of Dido Belle’ or ‘Belle: The Slave Daughter and the Lord Chief Justice’.

[3] The portrait was investigated in the BBC’s Fake or Fortune? in 2018, where Philip Mould was able to dismiss the previous attribution to Johann Zoffany (1733-1810).

[4] This account of Dido’s mother was taken from Thomas Hutchinson, the former governor of Massachusetts who saw Dido at Kenwood House in 1779