By Emma Rutherford |

20 Jan 2025

Catherine Da Costa's Studies of Insects

London, 1679 - 1756

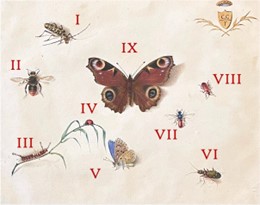

STUDIES OF VARIOUS INSECTS

Signed with the artist's initials within an armorial device u.r. C.C. / F.

Bears inscription to mount l.r. M. da Costa

Tempera on vellum

PROVENANCE:

Possibly Left by the artist in her will to her son, Abraham da Costa (d.1760, London) 2;

By whom left in his will to one of his surviving sisters;

With Galerie Ratton Ladrière, Paris (by 2006), from whom acquired by the present owners; Private Collection, London

This work *NOW SOLD* was presented for sale by Tom Mendel of the Nonesuch Gallery and Emma Rutherford of the Limner Company and is available to view online here. They are grateful to the following for their generous assistance:

Dr Henrietta Ryan, Dr Kim Sloan, Dr Susan Sloman and Dr Tabitha Barber

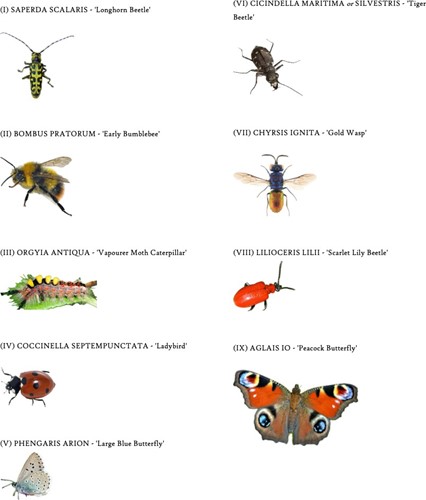

In the autumn of last year, I was shown an extraordinary work on vellum of detailed studies of insects [Fig.1]. Excitingly, the study, which was just slightly larger than a modern A5 piece of paper, was inscribed with a name she knew well – Catherine da Costa. Intriguingly, at the top right hand side of the page was a coronet, under which a shield held the letters ‘C.C/ F’, framed with two palm fronds – likely standing for Catherine Costa/ Fecit (‘she made it’). The palm fronds framing this vignette also began to make sense when I decoded them as a symbol of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, a Christian saint martyred in the early fourth century [Fig.2/ 2A].[1]

Although at first glance this work of art has little to do with the portrait miniatures The Limner Co. usually researches, the artist Catherine da Costa is best known as working in this medium. Da Costa’s her known output is a series of small portraits of family; idealised allegorical women and suitably Christian subjects such as the Penitent Magdalen. Da Costa studied under the Royal Limner, Bernard Lens III (1682-1740), as noted by the ever-observant George Vertue; 'One of the Da Costa Jews daughters learn't to limne of Bernard Lens for many years she having begun about 1712 continued to 1730...'.[2]

The tiny creatures on the page of this present work posed something of a puzzle. Usually an artist presents a distinctive technique which can be followed through their oeuvre – here was a study that was simply head and shoulders above any extant work by da Costa in terms of quality, composition and originality. The textures depicted in watercolour – from the velvet-soft butterfly in the centre to the miniscule hairs on the ‘fur’ of the bumblebee’s body – plus the careful shadows under each insect, were not only of a high quality compared to the known works by da Costa, the painting exceeded many other artists working in this period full stop. I consulted art historian and dealer Thomas Mendel, who runs the Nonesuch Gallery in Mayfair, London and has a special interest in the illustration of the natural world from artist’s working in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Thomas pointed out that this outlier of an artwork was also unusual for the period in which da Costa was working. As a fascinating intersection between 'Still Life' painting and botanical illustration, it was quite unlike the clunky copies made under Lens’s careful instruction. The composition is likely indebted primarily to the Flemish painter Jan van Kessel the Elder (Antwerp, 1626-1679), whose delicate small-scale paintings of insects and fruit could be found in noble and royal collections across Europe by the time Catherine began to paint. Artist’s such as van Kessell were highly skilled – not least because their presented in the sorts of cabinets created to display artworks which demonstrated the owner's worldliness in their kunstkammer (or 'cabinet of curiosities') [Figs 3/4/5/6].

Fig. 3 Three Butterflies, a Beetle and other Insects, with a Cutting of Ragwort, early 1650s, oil on copper, 9 x 13 cm, Jan Van Kessel I (1626-1679) - Ashmolean Museum, Oxford [acc. no. WA1940.2.42]

Fig. 3 Three Butterflies, a Beetle and other Insects, with a Cutting of Ragwort, early 1650s, oil on copper, 9 x 13 cm, Jan Van Kessel I (1626-1679) - Ashmolean Museum, Oxford [acc. no. WA1940.2.42] Fig. 5 Butterflies, Moths and Insects with Sprays of Common Hawthorn and Forget-Me-Not, 1654, oil on panel, 11.8 x 14.7 cm, Jan van Kessel I (1626-1679) - The National Gallery, London [inv. no. NG6666]

Fig. 5 Butterflies, Moths and Insects with Sprays of Common Hawthorn and Forget-Me-Not, 1654, oil on panel, 11.8 x 14.7 cm, Jan van Kessel I (1626-1679) - The National Gallery, London [inv. no. NG6666]As well as being an astonishing insight into da Costa’s skills as an artist, it also provided a new understanding of her international network of connections. She had had a privileged start in life – she was born at Somerset House, then the Royal residence of Queen Catherine of Braganza (1638-1705), the Portuguese wife of King Charles II. Catherine's Portuguese father, Dr Fernando Mendes (d.1724), was the physician to the Queen and had converted from the Jewish faith to Catholicism, though he maintained close ties with the Anglo-Jewish community throughout his time in London [Fig7.].

Catherine married her cousin Moses da Costa, a successful banker and merchant, and they lived together at the grand Cromwell House in Highgate, near other distinguished members of the Jewish community and gentry. The Mendes da Costa side of the family had prospered enormously following their emigration to Britain, and their annual income equalled that of much of the English aristocracy. Catherine's daughter Leonora also married into a phenomenally wealthy family of Portuguese-Jewish extraction, the Lopes de Suassos, who could boast enough money to loan William of Orange two million guilders to finance his voyage to London to claim the British throne.[3]

Catherine’s place in society clearly opened avenues not available to other women, particularly women artists. She likely knew Sir Hans Sloane and Dr Richard Mead who created small-scale private museums which included cabinets of curiosities, together with antiquities, impressive libraries and large portraits in oils including items from the owner's collections. As her teacher was also the Royal Limner, Bernard Lens III (1682-1740), this may have aided the access to collections with similar insect studies.

When researching this impressive work, Thomas gathered as many artworks by da Costa as he could find, including rarely-seen later paintings on vellum now in Amsterdam at the Joods Historisch Museum [Fig.8]. Here, it was clear that Catherine had later surpassed her master Lens, producing ambitiously large and detailed watercolour portraits on vellum of her daughter and grandchild. Here was the answer to the discrepancy between her early works under the instruction of Lens and this eminently superior study of insects. Dated to circa 1745, almost three decades separated these artworks and Catherine’s progress was clear. It is likely that, with this study as a benchmark, further works will come to light showing just what Catherine could achieve.

In May 2025, The National Gallery of Art in Washington will open an exhibition entitled ‘Little Beasts; Art, Wonder, and the Natural World’. Although it was too late to include the present work, it will certainly alert scholars to the oeuvre of da Costa and her new importance as a highly skilled artist in this field.

[1] George Vertue, B.M. Add Mss. 23079 f.26, printed in full in The Walpole Society, vol. XXII (Vertue III)

[2] Reportedly, Leonora's husband Francisco refused to accept any collateral for this massive sum, saying: “If you succeed, I know you will repay me; if you do not, I agree to lose the money.”