By Emma Blane |

22 Jan 2026

Rosalba Carriera (12/01/1673-15/4/1757): Friend, Artist, Pioneer.

Rosalba Carriera’s lively, highly-coloured and distinctive portrait miniatures have been somewhat sidelined by her later biographers. She is best known to the art world now as a pastellist, and there are various volumes on her and her work in this form. In most of these, her work as a miniature painter is mentioned, though few studies have been dedicated entirely to her pioneering paintings on ivory[1]. The article below is inspired partially by four miniatures handled by The Limner Company over the past two years, and partially by the fact that few publications on the work of Carriera, especially that focus on her work in miniature, have been written in English[2].

The pastel portraits of Carriera are well-recognised for good reason, and they feature in important public and private collections across the world, including the Royal Collection, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden[3], and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Considering the fragility of the medium, it is impressive that so many of these portraits have lasted so long. This may have been helped by the fact that Rosalba presented these framed in order to protect them. Alongside her works in pastel, one can also find portrait miniatures in these collections, and the subjects of these range from myths to formal portraits. Looking through those illustrated in Bernardina Sani’s monographs, and recorded in the photographic files of the Witt Library, Heinz Archive and Library, and the Netherlands Institute for Art History, it became clear that the scope for creativity and playfulness within these miniatures was much greater for Carriera than it was in her work in pastel. Here, I will discuss this in relation to four examples, and suggest some possible reasons for this increased creativity, placing this within the context of Carriera’s success as an artist and strong network of colleagues, students, and patrons in the Venetian settecento.

Carriera’s early life

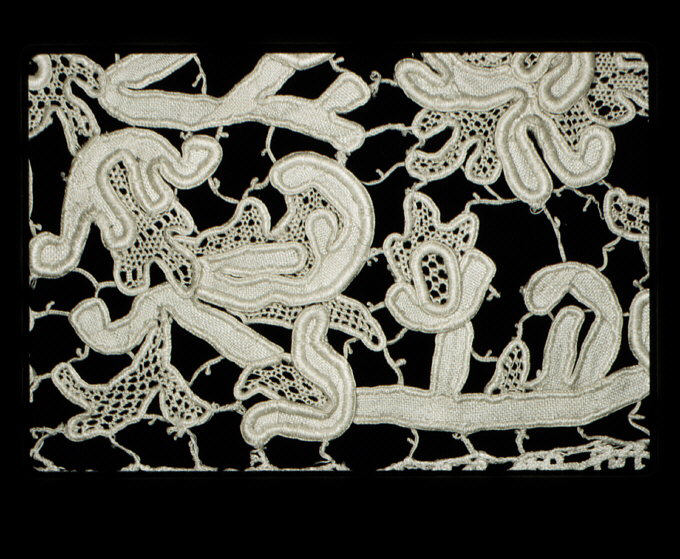

Carriera was born to a lawyer and a lace maker, and was the oldest of three sisters, Giovanna (1675-1737) and Angela. They grew up on the Grand Canal, and Carriera’s first employment in any form of art or craft came through her mother. She was a maker of Venetian lace, and it is said that Rosalba was particularly talented at making this. It is not surprising that she was able to adapt her skills to the delicate mediums of pastel and miniature painting if she was so adept in creating this fine material. Furthermore, and as will be seen below, Rosalba used her knowledge of lace within her portraiture, and this allowed her to add an extreme level of informed detail to the lace depicted in the costumes of her sitters.

Fig. 1: A Fragment of Venetian Lace, first quarter 18th century, Metropolitan Museum, New York, number 88.1.6.

Angela Carriera married Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1685-1741), another famed Venetian artist, in 1704. This marks one of the first ties between her and the wider network of art and artists in the Venetian settecento. Alongside Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734), Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto (1697-1768), Jacopo Amigoni (1682-1752), Pietro Longhi (1781-1785), and Luca Carlevarijs (1663-1730), Pellegrini was one of the great (male) artists of his generation working in the city. As a hub for tourism, they all had access to the patronage of not only Italians but also global clients.

For Pellegrini, it was the English Charles Montagu (1656-1722), 1st Duke of Manchester, who eventually moved him to England to work on the walls and ceilings of his home, Kimbolton Castle. When Manchester arrived in Venice in 1697 as Ambassador, his secretary was Christian Cole (1673-1734), who had an interest in art and is reported to have been a pastellist himself[4]. He is a relevant character as he became a friend to Rosalba, possibly through Pellegrini, and eventually supported her in applying to the Accademia di San Luca in Rome in 1705.

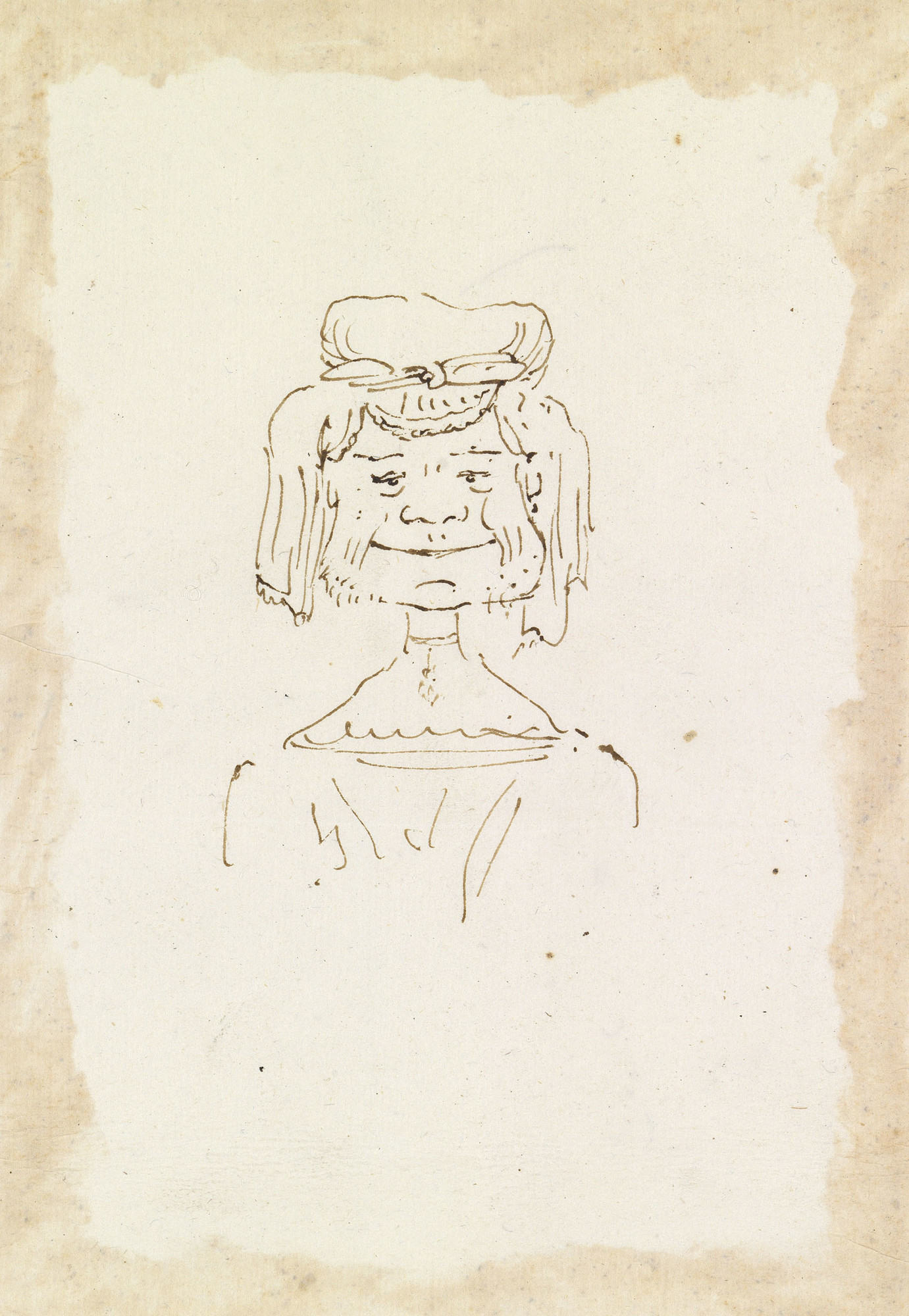

Fig. 2: ANTON MARIA ZANETTI THE ELDER (1680-1767), Rosalba Carriera c. 1730-40, pen and brown ink, 20.2 x 14.0 cm (sheet of paper), Royal Collection, RCIN 907390.

As Rosalba’s career developed, she fostered more friendships and relationships with other artists and influential figures across Europe. In Venice, one of these was Anton Maria Zannetti the Elder (1680-1767), who was clearly close to Carriera, given the existence of an amusing but brutal caricature of her now in the Royal Collection (fig. 2). Elsewhere, she maintained a friendship with Antonie Watteau, whom she had met in France in 1720, where she had been invited by Pierre Crozat (1661-1740) and Felice Ramelli (1666-1741), who was a student as well as a friend. Despite her close male friendships,, Carriera never married. There have been numerous theories as to why this was the case, many explained by Oberer (2023), including a suggestion that she was a lesbian and theories about her beauty (or lack thereof[5]). Neither of these seem to provide a factual basis for Carriera’s marital status. Perhaps she just never wanted or had time to find a husband, just as Canaletto never found a wife.

The Emergence of Carriera’s Miniature Painting

Carriera’s artistic career emerged in her late 20s; her first great professional ‘success’ in miniature painting was the Girl with a Dove[6] submitted to the Accademia di San Luca, Rome in 1705. Her work was well received, and she was admitted to the academy on merit, a first for a female artist. It has already been mentioned that Christian Cole was one of the people who pushed Carriera to go for this position and to move away from the purely commercial painting of miniatures for snuffboxes that she had focused on before this time.

The Girl with a Dove is not completely separate from her early works, which were popular for their depictions of young peasant women. A leaf through any catalogue featuring Carriera’s works will reveal numerous miniatures of these types; other famous examples include The Peasant Girl in the Uffizi. Referred to by Rosalba and contemporaries as ‘Fondelli’, these portraits were painted on the inside of ivory snuffboxes, decorated with pique on the lids. Many of Carriera’s later works still featured this decoration on the reverse (see figs. 3 and 4), likely because she sourced her ivory for painting miniatures from the same workshops producing these snuffboxes.

Fig. 3: Reverse of ROSALBA CARRIERA, Portrait miniature of a lady in Venetian dress, c.1710-20, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, oval, 3 5/8 in. (94 mm) high, sold by The Limner Company.

Fig. 4: Reverse of ROSALBA CARRIERA (Venice 1673 - 1757), Portrait of Joseph Smith and Catherine Tofts as Thalia, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, oval, 3 3/8 x 4 1/2 in (8.5 x 11.5 cm), researched by Stephane Renard, Mrs. Bożena Anna Kowalczyk, attribution confirmed by Bernardina Sani.

As hinted earlier, Carriera’s work on ivory is praised as the first of its kind. This is not to say that no one had painted in watercolour on ivory before; examples of other snuffboxes from the seventeenth century from the Ca ’Rezzonico’s 2023 exhibition show this was common form of painting, however these are very primitive in comparison to Carriera’s artworks. What was distinctive about Carriera’s approach was her removal of fondelli from their boxes, and development of portraits in their own right on this scale. In her diaries and letters, she referred to these portraits as miniatura; placing them into the same genre as the works of Nicholas Hilliard, Samuel Cooper, and other great artists who had come before her. Patrons soon began to request larger pieces of ivory that would ‘serve for a cabinet and not for a snuffbox[7]’, indicating that she was now producing pieces in their own right.

Some examples of miniatures by Carriera

Fig. 5: ROSALBA CARRIERA (1673-1757), Rinaldo and Armida, circa 1715, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, associated silver frame, oval, 3 1/8 x 2 3/8 in (8 x 6 cm).

Possibly one of the earliest of the miniatures by Carriera is this scene depicting Rinaldo and Armida (fig. 5). This is one of two miniatures painted by Rosalba of the same subject, the other being in the collection of the Dukes of Devonshire at Chatsworth. They vary slightly, in that the Chatsworth miniature displays Rinaldo looking at Armida, whereas this version sees him looking at himself in the mirror Armida holds.

The story of Rinaldo and Armida comes from Torquato Tasso’s (1544-1595) epic poem ‘Jerusalem Delivered’ (‘La Gerusalemme liberate’), published in 1581. In the poem, Armida, Muslim woman, enters a Christian camp and falls in love with Rinaldo, after distracting and transforming the knights into animals using magic. The sixteenth song of Tasso’s poem describes the pair meeting:

‘A crystal mirror, bright, pure, smooth, and neat, (Un cristallo pendea lucido et netto).

He rose, and to his mistress held the glass, (Sorse, e quel fra le mani a lui sospese)

A noble page, graced with that service great; (A i misteri d'Amor ministro eletto)

She, with glad looks, he with inflamed, alas, (Con luci ella ridendi, ei con accese) Beauty and love beheld, both in one seat; (Mirano in vari ogetti un solo oggetto) : Yet them in sundry objects each espies, (Ella del vetro a sé fa specchio: ed egli)

She, in the glass, he saw them in her eyes (Gli occhi di lei sereni a sé fa spegli).’

It is known that Rosalba owned a copy of the poem, and therefore the inspiration to create miniatures depicting the pair may have come from her reading of this. It is known that she read and translated Judith Drake’s Essay in Defence of the Female Sex (1696) into Italian, and was hence somewhat of an intellectual. Her sister, Giovanna, was listed by Luisa Bergalli in her 1726 anthology of women poets (the first of its kind to be published by a woman), as a poet herself. Therefore, the importance of poetry was not unknown to Carriera, and, as was, Oberer discusses, the saleability of erotic scenes such as this[8]. Along with her portraits of unknown peasant girls, scenes such as this were popular additions to snuffboxes, and remained so well into the nineteenth century. Carriera’s depictions, usually of women, were never as explicit as these scenes would later become, but were still taboo enough to be hidden from prying eyes by lids.

The back of this particular miniature is unfinished, leading to the suggestion that it was not intended to be part of a snuffbox. Instead, as was probably the case with the other miniature of this subject[9], this miniature may have been bought by a collector or Grand Tourist to display, in full view, in their home.

Fig. 6: ROSALBA CARRIERA (1675-1757), Portrait miniature of a lady in Venetian dress, c.1710-20, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, oval, 3 5/8 in. (94 mm) high, sold by The Limner Company.

The portrait of a lady in Venetian Dress (fig. 6) was discovered by the Limner Company in 2024, and is exemplary of Carriera’s talent in capturing the textures of fabrics and fashion from the Venetian settecento. It has already been mentioned that Carriera first trained in lacemaking, and her knowledge of the patterns and nature of this material is clear in the lace cuffs and stomacher worn by the unknown woman in this picture. She was able to achieve the texture she did by applying both light washes of watercolour and heavier patches of impasto, particularly visible in the green and pink fabric that makes up the woman’s dress.

Fig. 7: Detail from ROSALBA CARRIERA (1675-1757), Portrait miniature of a lady in Venetian dress, c.1710-20, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, oval, 3 5/8 in. (94 mm) high, sold by The Limner Company.

Her zendale, or the black silk and lace hood, dominates the portrait. These items of clothing were both important in the everyday life of Venetians, and, most significantly, were worn with masks during carnival. Combined with a mask, the hoods provided a disguise, and were worn by both men and women to hide not only their identity but possibly their gender. Another miniature showing a woman in the same type of hood in the Wallace Collection[10] indicates the popularity of these accessories, or perhaps that Carriera had one in her studio for sitters to wear, if they wished.

We do not know who this woman was, but if she was a visitor to the serenissima, it is possible that she asked Carriera specifically to paint her in this outfit, as a symbol to anyone who saw the miniature that she was well-travelled. There are other known examples of portraits by Carriera in which sitters are painted in particularly Venetian costume, including a pastel of Charles Sackville[11], and the portrait of Catherine Tofts, painted alongside Consul Joseph Smith (fig.7). Furthermore, A miniature featured in the 2023 exhibition at the Ca’Rezzonico features a Venetian noblewoman accosted by a figure also in a zendale and, in this case, a mask[12].

Fig. 8: ROSALBA CARRIERA (Venice 1673 - 1757), Portrait of Joseph Smith and Catherine Tofts as Thalia, watercolour and bodycolour on ivory, oval, 3 3/8 x 4 1/2 in (8.5 x 11.5 cm), researched by Stephane Renard, Mrs. Bożena Anna Kowalczyk, attribution confirmed by Bernardina Sani.

A unique miniature in Carriera’s oeuvre is a double portrait of Consul Joseph Smith (1682-1770) and Catherine Tofts (ca. 1685 - 1756), in the guise of Thalia (fig. 8). This miniature was discovered and researched by Stephane Renard, with the help of Mrs. Bożena Anna Kowalczyk, and the attribution to Carriera has been confirmed by Bernardina Sani, and we are indebted to all three for the information we have on this miniature. It was possible to identify merchant-come-art collector-come-agent Joseph Smith from a comparison with a portrait by Giovanni Grevemboch (1731-1807)[13], and the identification of Tofts comes from the fact that the two were in a relationship when the miniature appears to have been painted, around 1715. The pair were married in 1717, and this portrait therefore documents the beginning of their love story. It has been suggested that Tofts is dressed as Thalia, the muse of comedy, because of the mask that she holds in her hand. It has also been suggested that the mask could be a hint towards the fact that Tofts moved to Venice to escape creditors- and that this is a disguise in order to hide from them. It also references her career as an opera singer, a career in which costume was often worn.

The sitters in this miniature are representative of Carriera’s network in Venice. Smith was an agent to her, and Canaletto, as well as a patron, as it is assumed that this portrait was painted for him personally. By developing connections with figures such as Smith and Cole, it is clear that Carriera was able to develop personally and financially. But, as the existence of this miniature also proves, she was willing to honour these friendships by producing wonderfully creative works of art, like this miniature, that would have been close to the heart of those depicted.

Fig. 8: ROSALBA CARRIERA (1673-1757), Portrait miniature of a Gentleman wearing armour breastplate and blue cloak, holding the Coronation Medal of George I, circa 1715, watercolour, bodycolour and gold paint on ivory, later silver-gilt frame with blue enamel border, oval, 75 mm. (2.9ins) wide, sold by The Limner Company.

Oberer (2023) has suggested that Carriera’s sittings with male clients would have been more heavily monitored than those with female clients[14], and this could be a reason for there being both fewer portraits of men by her, and the fact that these are, on the whole, less elaborate in their costume and scenery. The above portrait, also sold by the Limner Company, is another unique example from her oeuvre, in the fact that it does contain some more interesting details, largely in the object that the sitter holds. This is the Coronation medal of George I. Again, the sitter remains anonymous, but it is suggested that he was an English visitor to Venice on the Grand Tour and that he is holding the medal as a proud recipient. The miniature is also unique in its format- the horizontal oval is the same as that of the portrait of Smith and Tofts, but as far as the author has been able to find, this is the only example of a single male portrait in this format by Carriera.

Certainly, in comparison to some of her portrait miniatures of men, including that of an unknown man in the Metropolitan Museum (no. 49.122.2), and the portrait of Christoffel Bernhard Julius von Schwartz in the Rijksmuseum (SK-A-4032), this portrait has more depth and intrigue. It is also more unique in providing an object through which, at the time, this gentleman would be more easily identified. Other miniatures of gentlemen by Carriera have similar objects of intrigue, such as the snuff box held by the gentleman in her portrait identified as the Young Pretender[15], but these are nowhere near as common as they are in both miniatures and pastels depicting female sitters.

Carriera as a woman’s woman

To lead on from this note that Carriera’s portraits of women are on the whole more creative than those of men, it is important to discuss her attitude towards her own gender that became apparent throughout Carriera’s career. It has already been seen that Carriera was supported by multiple male figures in her art, but it is also clear that she was keen to help other, younger women develop their own skills and to become artists in their own right.

Rosalba and her sister Giovanna were two of only seven miniature painters in Venice, as recorded by Vicenzo Corelli in 1697. It is assumed that Giovanna was trained by her sister, and she was to become one of many women involved in Carriera’s studio. Her other students included Felicita Sartori (b.1713), and Marianna Carlevarijs (1703-1750), daughter of the famed view painter Luca. Her students were trained in both miniature and pastel, and it is tempting to think that Carriera purposefully employed women. Of course, their presence in the studio would have also been influenced by the assumption that miniature painting was a ‘feminine’ art. Furthermore, Carriera also had male students, including the aforementioned Felice Ramelli. Whether purposeful or not, her employment of these women did give them a step-up in their careers.

This sense that Carriera put more creative energy into painting women in outfits decorated with flowers and in allegorical guises goes hand in hand with the idea that she was a supporter of women, or a woman’s woman. As is demonstrated by her oeuvre, there were plenty of gentlemen willing to wear costumes. It was perhaps easier for Carriera to relate to, and feel a willingness to, paint portraits of women in these even when they were strangers, whereas she was only happy to do this for men if they were already friends.

The end of Carriera’s career

In the 1720s, Carriera’s focus moved more towards producing pastel portraits, and she produced fewer and fewer miniatures. By 1724, she had begun to experience issues with her vision, meaning it was almost impossible for her to work in this smaller medium. Health conditions like this were not uncommon amongst artists and miniaturists. She underwent two painful cataract surgeries in 1746 and 1751. Unfortunately, neither worked, and she died six years later. At this point, she had lost her sister, Giovanna and was being cared for by Angela. One testament to the success of her career at her death was the 24,556 Zecchini, including investments, that she left behind. This was significantly more money than the legacy of herher male counterparts[16].

Carriera’s footprint is certainly very clear in the history of miniature painting. For the following centuries, ivory remained the most popular support for these portraits, and their intimate and jewel-like nature continued to capture the hearts of sitters and recipients across the globe. Her works capture the intricate artistic networks of Settecento Venice, as well as providing an insight into the place women held as professional artists in the rococo period.

[1] This is said except for a select few publications, including the catalogue produced to accompany the Ca’Rezzonico’s exhibition ‘Rosalba Carriera: Miniature su Avorio’, held between October 2023 and January 2024, and curated by Alberto Craievich, and C J de Bruijn Kops’ 1988 article, published as part of the Bulletin of the Rijksmuseum.

[2] One of the most informative English-language works on Carriera’s life was written by Angela Oberer as part of the Illuminating Women Artists: The Eighteenth Century series. See A. Oberer, Rosalba Carriera, Los Angeles, Getty Publications, 2023.

[3] The Kunstsammlungen Dresden has one of the largest collections of works by Carriera,

[4] N. Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1900, online edition, ‘COLE, CHRISTIAN’.

[5] Many of the contemporary comments on her beauty are typically misogynistic for their time. Carriera was seen by others as a talented artist, though there was often a ‘but’ relating to her attractiveness linked to this, possibly linked to a sense that only a woman with male qualities could ever have as much talent as this.

[6] Still in the collection of the Accademia di San Luca, illustrated Sani, Rosalba Carriera, 2007, cat no. 16, p. 70.

[7] Quote from Francesco Stiparoli in 1715, cited by B. Falconi, ‘Rosalba Carriera e la miniatura su avorio’, in Rosalba Carriera, Convegno Internazionale di Studi, Venice, Fondazione Giorgio Cini; Chioggia, Auditorium San Nicolò, 26-28 April 2007.

[8] Oberer, 2023, p.29.

[9] Which is believed to have been brought back from Venice by Lord Burlington by 1715.

[10] Rosalba Carriera (1673 - 1757), An Unknown Lady in an Italian Dress, circa 1710-1720, Wallace Collection, London, collection no. M310.

[11] Sani, 2007, no. 321. At that point, this pastel was still in the collection of Lord Sackville, Sevenoaks, Kent.

[12] A. Craievich, Rosalba Carriera: Miniature su Avorio, Scripta, Venice, 2023, cat. no. 34. Private collection.

[13] GIOVANNI GREVEMBOCH, Portrait of Joseph Smith, 1754 - 1759. Pencil and watercolour on paper, 28x20 cm. Page from Gli abiti de' veneziani di quasi ogni età con diligenza raccolti e dipinti nel secolo XVIII, Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici Veneziani, Correr Museum Library, MS Gradenigo-Dolfin 49, II, fol. 125.2.

[14] Oberer, 2023, p.38.

[15]Based on the reproduction seen by the author, the gentleman in this portrait does not look like the Young Pretender. This miniature is in the Louvre, Department of Graphic art, RF30678.

[16] Oberer, 2023, pp.116-117.