By Emma Rutherford |

19 Jan 2026

‘A force of expression quite out of the ordinary’; A rare portrait miniature by Ismael ‘Israel’ Mengs, Saxon Court Painter (1688-1764)

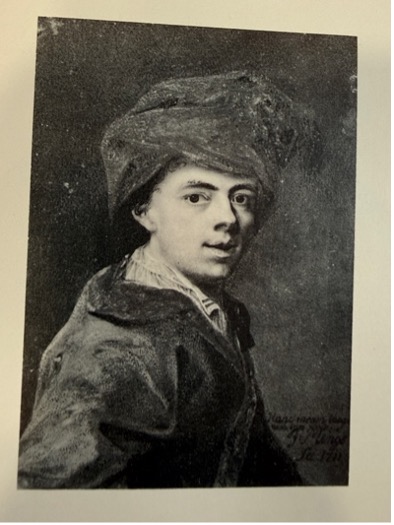

Fig. 1

Ismael Mengs, Self-portrait, watercolour and bodycolour on vellum, signed and dated 1711 (now lost),

reproduced from black and white photograph in Schidlof, ‘The Miniature in Europe’, 1964, pl. 812.

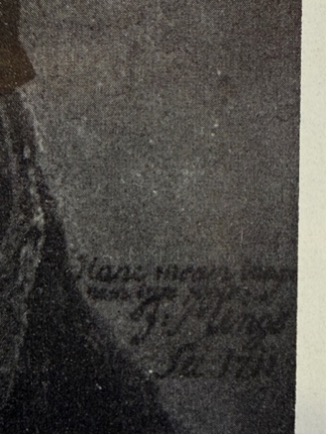

Fig. 2

Ismael Mengs, self-portrait in Polish Costume, circa 1714

Watercolour on parchment

Dimensions 9.3 x 7.4 cm

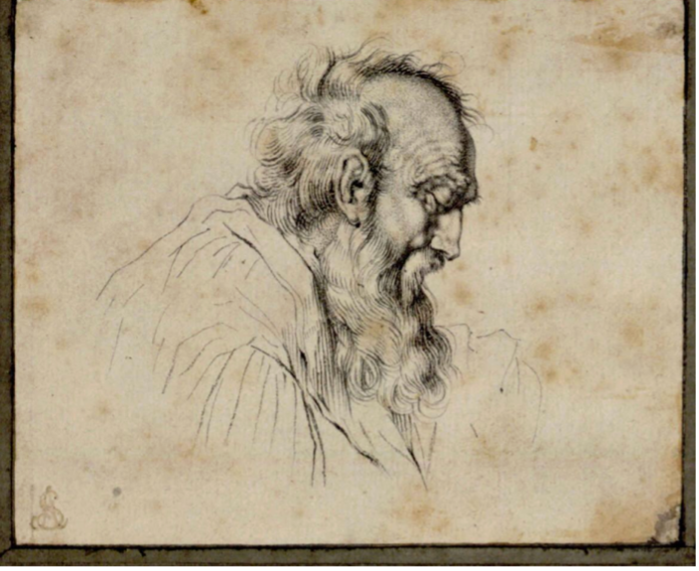

Now lost, this 1711 self-portrait, painted as a miniature on vellum, probably travelled with the young artist to showcase his skills. Originally from Lusatia – a region split between Poland and Germany - its companion piece was likely this rare character portrait – also known as a tronie[1] - of an elderly man wearing a fur hat. Also dated 1711, this portrait would have had the ability to convey that Mengs could take portraits from the life (as in his own self-portrait) but also the character studies required for history paintings. Another rare survival of a sketch by Mengs, also of an elderly man, is in the collection of the Albertina, Vienna (fig.4). As Andrea Lutz observes ‘Their closeness to reality and immediacy are of almost timeless validity, which makes the virtuously painted faces seem appealing and topical even today.’[2]

Fig. 3

Ismael Mengs, An Old man wearing a fur-trimmed hat, signed and dated 1711

Watercolour and bodycolour on vellum

The Limner Company

Fig 4.

Head of an Old Man

Drawing on paper

7,8 x 9,4 cm

Albertina, Vienna

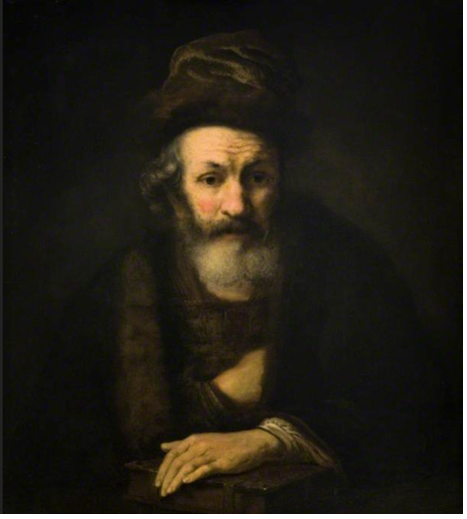

The image of this old man recalls the work of artists such as Rembrandt (1606-1669), who enjoyed painting tronies in the early to mid-17th century. Such studies allowed a degree of freedom on the part of the artist – a way to experiment with facial expressions which went beyond the stillness of a commissioned portrait. There was also freedom in the costume – with fantastical and eclectic dress from the artist’s imagination shown in such works. While they were often used for study and employed as practice during an artist’s apprenticeship, they were also created as independent works for the art market. By 1711, this type of artwork was beginning to go out of fashion. Here, Mengs looks back, possibly to the work of both Anthony and Abraham van Dyck (1599-1641) and (1635/6-1672) respectively. Particularly close are Anthony van Dyck’s tronies of men with beards and Abraham’s painting of ‘A Bearded Man in a Fur Hat with a Book’ (Burrell Collection).

Fig. 5

Abraham van Dyck (c.1635–1672) (attributed to), A Bearded Man in a Fur Hat with a Book

The Burrell Collection

Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Portrait of Painter Martin Ryckaert (1587-1631)

Prado, Madrid

Ismael was a fascinating character – he was a rebel, who lived outside societal norms. He changed his religion as often as he moved from country to country and yet he has been eclipsed by his son.

His longstanding affair with his housekeeper, Christiana Charlotta Bornmannin (1703-1731), produced four children, but the couple did not marry until near the end of her life in 1729. This unconventional relationship caused many issues, including the status of these illegitimate children. Whenever Christiana was pregnant, her and Ismael rented a house in Ústí nad Labem, Mírové Square, where they stayed until his wife gave birth. When the time came, Ismael Mengs visited the mayor, gave him a gift for the city’s needs, and requesting that he became the godfather of his children. He confirmed that they were born within marriage and were properly baptized in the Roman Catholic faith at the church in Ústí nad Labem. However, even the artist’s religion is still a matter of debate – long known as a Jewish artist, he became a Lutheran around 1710. Philipp Weilbach, in the Encyclopaedia of Danish artists stated that his ancestors had emigrated to Denmark from the Lausitz, Germany. Whether Ismael's parents had already embraced the Protestant religion, or whether the son took that step, had never been determined.

Ismael’s artistic career was long and varied but produced relatively little. Initially, he trained where he was born in Copenhagen – as a pupil of B. Coiffre – before moving to Lübeck. Around the time this portrait miniature was painted, he was in Hamburg, moving in 1713 to the court of Mecklenburg (where the future Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, would be born in 1744). He travelled widely during these years – moving to both Dresden and Leipzig and visiting Italy. Before his court appointment in Dresden, he likely painted another self-portrait on parchment showing himself in the typical dress of a Polish nobleman (complete with heron feathers in his hat). Able to work in enamel – as well as painting portrait miniatures on vellum and ivory – he was useful as a court artist. Portraits of Augustus II, the Strong (1670-1733) (he would show his strength by bending horseshoes and tossing foxes), Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, made in enamel, were part of his output.[3] A group of religious miniatures painted on ivory and in enamel also exist, probably conceived as a set, in the Dresden Gemäldegalerie. Nothing, however, seems to have surpassed his 1711 self-portrait, described by Schidlof as having ‘a force of expression quite out of the ordinary’ and the small tronie painted in the same year.

Fig. 7

Anton Raphael Mengs (1728–1779), Self-Portrait at Twelve Years Old, 1740

Black and red chalk

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 2464

After working for some time at the court of Augustus III, Ismael turned to teaching at the Academy in Dresden where he became director. This led him to the most important role of his career – as the tutor for his son, Anton Raphael (1728-1779), now thought of the as the preeminent artist of the Neoclassical period. Named after two of his father’s favourite artists (Anton for Antonio Allegri, better known as Correggio), Anton Raphael later noted his father’s strict upbringing and tyrannical training regime. Interestingly, Ismael taught his son through the copying of portraits by Anthony van Dyck, who his considered to be one of the greatest artists who had ever lived. In the mid 1750s, when Anton was at the height of his fame, to paint a portrait in the manner of van Dyck was considered a testament to an artist’s ability – judging from the existence of this small tronie, which is certainly painted with van Dyck in mind, little had changed in terms of admiration for this artist from the previous generation. Like his father, Anton also lived an unconventional life, marrying a girl who sat for him as a model called Margarita Guazzi, with whom he had twenty children and becoming friends with the notorious libertine Giacomo Casanova.

The emergence of the rare portrait miniature of an old man by Ismael Mengs comes at a time when his son’s work is undergoing review – with a comprehensive, monographic exhibition at the Prado in Madrid.

[1] The word ‘tronie’ is Dutch for ‘face’.

[2] Lutz on the exhibition ‘Portrait Tales – Portrait and Tronie in Dutch Art’. Exhibition: 11 March - 5 November 2023, Kunst Museum Winterthur, Switzerland.

[3] One enamel version exists in the Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Dresden, and another is noted in the Louvre, Paris by Schidlof.