By Emma Blane |

13 Nov 2025

A Closer Look: William Horace Beckford, later 3rd Baron Rivers (1777-1831), painted by his sister, Harriet Beckford, later Ker Seymer (1779-1853)

HARRIET BECKFORD, later KER SEYMER (1779-1853), after Richard Cosway (1742-1821), Portrait miniature of William Horace Beckford, later 3rd Baron Rivers (1777-1831); 1802 , watercolour on ivory (licence 1RVZQBQS), oval, 8.7 cm (3 ⅖ in.) high.

Some context

Despite the original portrait having been drawn in 1790, the portrait miniature by Harriet was not painted until 1802. The most likely explanation for this is that Harriet did not see, or did not feel capable enough to copy, this drawing until a later date. Harriet had spent some time in Italy, alongside her brother and father, in the 1790s, and it is possible that she had not actually returned to England until the early 19th century- more on this later.

The earliest provenance we have for this miniature is a 1980 sale (Sotheby’s, London, 24 March 1980, lot 151), and it is known that it was in the collection of Dr Erika Pöhl-Stroher until 2025. Before then, the miniature cannot be traced, though it would have remained within Harriet’s family collection for some time.

The Beckfords

One of the largest controversies of Horace’s and Harriet’s side of the Beckford family was related to the incompatible marriage of their parents[4]. In the late 1770s, Lousia had begun an affair with her husband’s cousin William Beckford, and she often attended Fonthill without her husband. Numerous letters between the pair exist, outlining their love for each other and Louisa’s dislike of her husband and his lifestyle. The affair ended following William’s departure to Italy in 1782, and his marriage in 1783.

Following the end of the affair, Peter took his family to Italy. They would remain here between 1776 and 1799. In Italy, they lived in Pisa and Florence, and visited numerous other cities. Following their (not so brief) excursion, during which Louisa had died from consumption, they returned to Britain.

Harriet Beckford as an artist

In 1797, it is recorded that Harriet was a member of the Accademy of Fine Arts (Accademia di Belle Arti) in Florence, where her family were living at the time. In attending the Aaccademia, she was not only following in the footsteps of some of the greatest female artists of the period, including Maria Cosway (1760-1838) and Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807), but also some of the greatest miniature painters of the period, including Nathaniel Hone (1718-1784) and Ozias Humphry (1742-1810). It was probably here that Harriet learned to copy the work of masters in order to develop her own skill, and possibly came across some of the works that she would later go on to copy in miniature form[10].

As an artist, Harriet is exceptional, and Schidlof (1964) states that she ‘deserves to be better known’. Of course, part of the issue in this is that there are so few works known to be by her. Given that she has signed all of the known works, however, it is possible that others remain out there, waiting to be discovered. Her style is varied; clearly intended to imitate the work of those artists she is copying exactly. However, this in itself shows skill, and a keen eye that was able to pick up techniques and details used by others.

Harriet continued to paint after her marriage (assuming that the date on the Greenwich miniature is in fact 1809), to Henry Seymer, later Ker-Seymer, in 1807. A year before the marriage Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) was commissioned to portray Harriet, the result being a portrait currently with Rafael Valls[11]. However, there are no extant works produced after this date. Later in her life she developed a friendship with William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877), a pioneer in photography. The letters written by Harriet to Fox Talbot are some of the only records of her voice; they are often discussing her visits to him, or vice versa. The two do not, however, discuss the art of photography in their written correspondence. Only one letter mentions any art, being a discussion of returning the ‘Guercino’, likely to be a book of prints[12], that had been lent to Harriet by Fox Talbot.

Horace married only a year after his sister, in 1808, his wife being Frances Rigby. The financial situation of the family does not appear to have been great before the death of Harriet and Horace’s father in 1811, and would certainly not have been made any better with the debt piled up from Horace’s gambling and attendance of clubs. This appears to have been an issue even before he was married, as a letter, published (undated) in the Beckford Journal, sees his maternal uncle, Lord Rivers, insist that he must quit his gambling [sic] until he is married. In the same letter he also threatens Horace that ‘You are only Heir to the title:- but my Estate is perfectly in my own Power.[14]’. It was from his mother’s family, after all, that his title, and some of his inheritance, would come. His mother had only one brother, the author of the above letter, George Pitt, 2nd Baron Rivers (1751-1828). He had no children.

When it came to inheritance, the threat of Horace’s uncle held true. It seems that the estate was entrusted to Horace’s eldest son, George, 4th Baron Rivers (1810-1866), and his father was only given a yearly income, to avoid him wasting vast sums of money on his addictions. This was in 1828- these habits had clearly plagued Horace throughout his life.

Tragically, William Horace Beckford took his own life in 1831. He was found in the Serpentine, drowned. The incident is mentioned by Harriet in a letter to Fox Talbot, referenced to as ‘a sad and awful event[15]’.

It may be because of the location of the original drawing that Harriet did not copy it until a lot later on. Furthermore, Horace was given his title of 3rd Baron Rivers in 1802, the year the miniature was painted, and it may have been done to celebrate this.

Due to the size constraint of the miniature form, Harriet has only copied the top half of her brother in this portrait. It has been developed sensitively from the watercolour to include more colour, and a sky background- extremely popular in miniature painting of the nineteenth century. There is a remarkable level of detail in Horace’s hair, the feather on his hat, and- notably, the fine lace trim of his collar.

His distinctive and dramatic outfit is not dissimilar from one worn by Richard Cosway in a self-portrait in the British Museum[16]. In this other drawing, Cosway sits beside a book titled Vita di Rubens, referencing a possible influence of his style and fashion. Both Horace and Cosway are shown in Vandyke-esque collars, and Horace’s hair especially mimics the styles donned by Cavaliers of the seventeenth century.

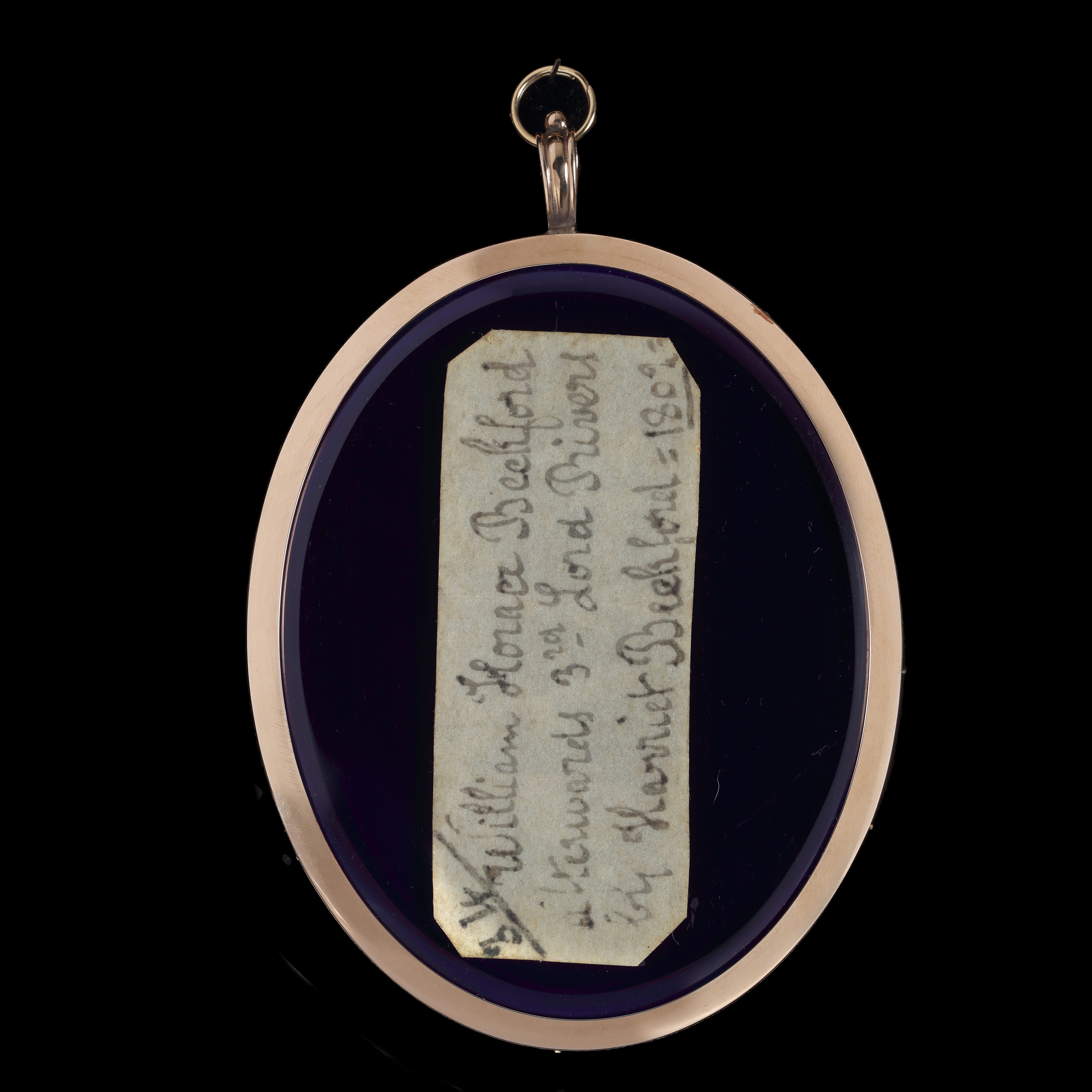

A comparison of this miniature to others by Harriet allows for a suggestion that these were once all displayed within the family’s collection. Most of these (where it has been possible to access an image of the reverse) have labels on the reverse, in the same writing, indicating the subject of the miniature (fig.3). They also have numbers on them- the present example being ‘34’, the Head of Niobe being ‘35’ and the copy of Kauffman’s Cupid being ‘39’. These miniatures would have probably been displayed in the family home, and these numbers would have been a reference to their place within the collection. Though it is nice to imagine, the other numbers, up to and following 30, would have probably belonged to other works of art, not by Harriet.

This portrait, by a sister, of her brother, provides interesting insights into the Beckford Family and the nature of miniature painting done by females in this period. Harriet had received artistic training, but did not use this to develop a profession, instead maintaining it as a hobby. Nevertheless, her works were kept alongside others owned by the family. In the case of this miniature, it was painted to commemorate a milestone in her brother’s life, and would remain a symbol of his youth, despite all that would change in his life in the years that followed.

Fig.2- Verso with label, HARRIET BECKFORD, later KER SEYMER (1779-1853), after Richard Cosway (1742-1821), Portrait miniature of William Horace Beckford, later 3rd Baron Rivers (1777-1831); 1802 , watercolour on ivory (licence 1RVZQBQS), oval, 8.7 cm (3 ⅖ in.) high.

[1] RICHARD COSWAY (1742-1821), Portrait of Horace Beckford (1777-1831), 1790, 9 1/8 x 5 5/8 inches (230 x 142 mm), Pencil and watercolour on paper., Morgan Library and Museum, New York (1956.14). Another verison was sold at Sotheby’s, 28th November 1974, lot 41, and has more detail. Though this other version is attributed to Cosway, it is not signed, and a suggestion that this drawing could be by Maria Cosway cannot be discounted, though it is difficult to make a certain attribution from available photographs. Maria was known to copy drawings by her husband.

[2] In previous centuries, feathers like this were worn by Landesknecht (for a good discussion of this fashion, see https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/when-men-wore-feathers), and Cavaliers in the seventeenth centry. The influence of the latter’s fashion will be discussed further below.

[3] It has to be noted that the majority of the Beckford fortune came from the Transatlantic Slave Trade. There is a more comprehensive overview of the family’s links in this article, published by Beckford’s Tower and Museum, Bath: https://beckfordstower.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Beckfords-and-Slavery-leaflet-2007.pdf.

[4] M. Ranson, ‘Peter Beckford Esquire of Stepleton, Dorset’, The Beckford Journal, ed. R. Allen, vol. 14, Spring 2008, p. 19.

[5] L. R. Schidlof, The Miniature in Europe, Graz, 1964, vol. 3, fig. 77, pl. 43.

[6] HARRIET BECKFORD, Emma, Lady Hamilton, watercolour on ivory, circular, 8.2cm diameter, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Caird Fund, MNT0127.

[7] The inscription is on the top right edge of the miniature and is therefore difficult to read. It appears that the date is 1809, even though Basil Long (1929) gives the date as 1803.

[8] HARRIET BECKFORD after ANGELICA KAUFFMAN, Cupid, oil (?) on ivory, 11.5 x 9.5cm, sold Cheffins, Cambridge, 26 June 2024, lot 316.

[9] HARRIET BECKFORD, Head of Niobe, watercolour on ivory, oval, 7.5cm high sold Cheffins, Cambridge, 26 June 2024, lot 317.

[10] There is no clear contender for the original portrait of Emma Hamilton, or of the rectangular portrait of the young girl praying, however it is likely that these were copies. The closest work after which the Emma Hamilton could be a copy is plate 9 of the print of Frederick Rehberg’s drawings of Hamilton in the British Museum (1873,0809.131-143).

[11] See https://www.rafaelvalls.co.uk/artwork/a-portrait-of-mrs-harriet-ker-seymour-seated-half-length-in-a-white-dress-her-left-arm-resting-on-an-orange-mantle/.

[12] This object is mentioned in a letter dated 12 December 1832 (British Library, Fox Talbot Collection, document number 465), from Harriet to Fox Talbot. A footnote on the online record of Fox Talbot’s letters suggests that this was a book of prints. See https://foxtalbot.dmu.ac.uk/letters/transcriptName.php?bcode=Ker-HA&pageNumber=16&pageTotal=17&referringPage=0.

[13] For a longer description of this trip see, M. Ranson, ‘Peter Beckford Esquire of Stepleton, Dorset’, The Beckford Journal, ed. R. Allen, vol. 14, Spring 2008, p.25.

[14] This letter is quoted, undated, in M. Ranson, ‘Peter Beckford Esquire of Stepleton, Dorset’, The Beckford Journal, ed. R. Allen, vol. 14, Spring 2008, p.27.

[15] Letter from Harriet Ker Seymer to William Henry Fox Talbot, dated 1 February 1831, British library, Fox Talbot Collection, document number 2137.

[16] British Museum, Prints and Drawings, 1857,0606.29.